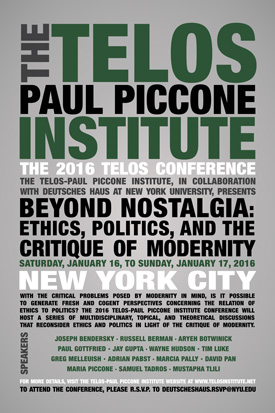

Kenneth D. Johnson is affiliated with the William J. Seymour Institute for Black Church and Policy Studies, in Boston. The following paper was presented at the 2016 Telos Conference, held on January 16–17, 2016, in New York City. For news about upcoming conferences and events, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

Introduction

Introduction

The spate of killings of unarmed African American males by police and vigilante residents[1] has continued to roil public opinion in the black community, leading to various forms of social protest, in particular by varied groups of young adult African Americans.[2]

Preeminent among these groups is #BlackLivesMatter, which now aspires to become a national movement, sometimes in coalition with other contemporary groups formed near the same time, and displacing older Civil Rights groups and the Black Church’s ethical and protest traditions.

While #BlackLivesMatter has partly instrumentalized Black Church social protest tradition,[3] it has done so in the service of a fundamentally secular set of ethical commitments. In the process, the #BlackLivesMatter movement has discarded the internal resources of self-critique that Black Church ethical praxis provides.

I hope to provide something that #BlackLivesMatter has thus far been unable to provide for itself: an external ethical critique that illuminates a few of the new movement’s challenges in its ethical praxis. In this way, we may offer a nobler path for this new secular political theology in the African American community.

Secular and theological? It may seem an oxymoron, but as recent discussions about the post-secular age have demonstrated,[4] and as Carl Schmitt long ago argued,[5] secular concepts may have theological origins, and theological concepts may be indebted to secular ones. The dialectical tension between, and sometimes synthesis of, these elements often arises in popular social movements, including that of #BlackLivesMatter. I will discuss the origins and aims of #BlackLivesMatter, its social ethics, and comment on its sustainability as a social justice movement.

The Origins of #BlackLivesMatter

#BlackLivesMatter arose due to the shooting death of Trayvon Martin in 2012 by vigilante George Zimmerman in Florida, and Zimmerman’s subsequent acquittal in his death. In 2013, three black lesbian women, Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi, created the Twitter hashtag and a website for #BlackLivesMatter.[6] These women were all college educated and involved with labor and political organizing.[7]

Early on, #BlackLivesMatter was deeply indebted to Queer Theory, the concept of intersectionality,[8] and the movement of “genderqueer” or gender nonconforming persons.[9] One of the program planks of #BlackLivesMatter is to put transgender persons, lesbians, and gay men at the front of what they describe as “(re)building the Black liberation movement.”[10]

The powerful, jarring meme of “Black Lives Matter” has combined with social media technology to facilitate the growth of formal and informal networks, allowing them to communicate rapidly and mobilize protest activities. Witness the efforts during 2015 to shut down Interstate highways to block traffic, or obstructing subway systems, and occupying large shopping malls, like the Mall of America in Minnesota,[11] as a means to attract attention and to insist that “business as usual” will stop until their demands are met.

Furthermore, #BlackLivesMatter gathers together many disparate activist groups, some predating #BlackLivesMatter and others created afterward, under the Black Lives Matter umbrella or as a result of local protests against perceived police misconduct.[12] There is a diffuse leadership, with different local chapters of #BlackLivesMatter. Different activists, sometimes working regular jobs, and sometimes working as paid organizers for other groups, can and do claim to speak for #BlackLivesMatter. The formal Black Lives Matter Network itself states that it is “not synonymous with the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Our network is one piece of a broad movement that spans a diversity of approaches, perspectives, and strategies.”[13]

What Are the Aims of #BlackLivesMatter?

What are the aims of Black Lives Matter?

This was initially unclear; however, finally in July of 2015 Black Lives Matter issued a list of twelve demands. It seeks, at a minimum, to end shooting of unarmed blacks by police and security guards, and other forms of police misconduct. It also has a laundry list of other items, such as education reform, full living wage employment, healthy food for black communities, decent housing and an end to gentrification, release of all political prisoners, an end to the military industrial complex, and an end to mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex.[14] Strangely, for a left-wing movement, it does not mention an end to capitalist neoliberalism or class struggle.

However, #BlackLivesMatter, guided by sex and gender identity politics, does seek radical changes in gender relations—an effacement of sex and gender entirely along the lines of the genderqueer movement.[15] This does not seem to have any direct or rational relationship to the deaths of blacks at the hands of police.[16] But under the rubric of intersectionality, that is, one’s inhabiting multiple oppressed states of race, class, gender, etc., and the need to have these coalesce into alignment with the multiple struggles against oppression of these group statuses; it seems that any number of disparate social movements could be amalgamated under the #BlackLivesMatter banner, just like the perennial marches of left-wing groups that advocate for almost every conceivable social justice issue under the sun.[17]

Where Does #BlackLivesMatter Get its Social Ethics?

#BlackLivesMatter does have a form of social ethics. While #BlackLivesMatter’s website states that it rejects what it describes as the “narrow nationalism”[18] that is sometimes found in other Black social movements, it also “centers those that have been marginalized within Black liberation movements.”[19] #BlackLivesMatter believes that women, trans, gay/lesbian, and disabled persons were relegated and marginalized in previous Black movements. They do not seem to reckon fully with the powerful contributions of black women Civil Rights activists like Diane Nash, Miss Ella Baker, Rosa Parks, Fannie Lou Hamer, and others who were seen and heard during the activism of the 1950s and 60s.[20]

Some of the #BlackLivesMatter adherents are hostile to Christianity in general and the Black Church in particular. A few of them seem to have read the arguments of secular European thinkers and became converted, as it were, to atheism. However, as an ostensibly pro-Black movement, it is not apparent why these young people would accept without question what these Enlightenment thinkers said.

A deeper interrogation reveals that far from a high-minded philosophic rejection of Black Christianity, some of the #BlackLivesMatter folks’ aversion to the Black Church is their perception of the Church’s conservative stance on issues of sexual conduct, sexual identity, and sexual presentation in daily life, specifically the status of gender nonconforming persons, transgender persons, and the presence of alternative sexual behaviors and expressions as a substitute for heterosexual conduct.[21]

Under normal conditions, these concerns would not need to feed into a rejection of the Black Church as a social movement partner, but under the doctrine of intersectionality, the politics of sexual identity and presentation serve to exclude anyone who does not toe the line. Thus, #BlackLivesMatter has used the issue of sexual and gender politics to sever any connection to the older Black Civil Rights Movement and its Judeo-Christian ethical resources. This estrangement has impoverished #BlackLivesMatter as a whole in terms of its tactics, optics, and end goals and the strategy to attain them.

Despite the rejection, #BlackLivesMatter does a theological borrowing around a notion of radical inclusivity for at least all black lives, with the use of the doctrine of intersectionality. This may be a borrowing, whether intentional or not, of St. Paul’s challenge to the ancient world’s notions of status and class distinctions as reported in the New Testament. St. Paul writes in his letter to the Galatians that “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free man, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”[22] In the hands of #BlackLivesMatter, this could mean a notion of care, and not merely a political statement. However, as #BlackLivesMatter has begun as a political, rather than a cultural movement, it is not clear how they intend to implement this consistently.

#BlackLivesMatter uses moral and ethical language, even while not acknowledging its indebtedness to the prior, church-based, Black Civil Rights movement ethics. #BlackLivesMatter thus far has been nonviolent, but says it rejects what they call the “politics of respectability,”[23] and in particular the notion of turning the other cheek. It does not effectively address how it will winsomely persuade an American society that it believes is fundamentally hostile to black lives.

#BlackLivesMatter offers external critique as one would expect from any social justice movement, but has not explicitly obtained the resources for its own self-examination, self-criticism, and self-correction that the earlier Judeo-Christian ethic of the Black Church and the Civil Rights Movement supplied. Nowhere is this ethical blindness more evident than in the consistent failure of the #BlackLivesMatter movement to address the overwhelming and disproportionate body count of deaths of blacks by other members of the black community who are not police, security guards, or vigilantes.[24] The greatest physical threat to black lives today is not from white cops, but rather from ordinary black residents themselves.

#BlackLivesMatter has failed to discern the dialectical relationship between unjust killings of blacks by police, and the unjust killings that occur by blacks against other blacks in black neighborhoods on a daily basis. The disordered state of the neighborhoods is related to the disordered relations with police. It is a distorted dialectic between the freedom of the residents, on the one hand, and authority as represented by police, on the other.[25] Without the Black Church ethic as a guide to interpret this dialectic, #BlackLivesMatter retains this contradiction and is unable to resolve it in a manner that preserves black lives.

#BlackLivesMatter’s omission of a serious engagement with this problem bespeaks an incompleteness of its ethical vision.[26] Clearly, in its practice, some black lives matter more than others.[27]

Is #BlackLivesMatter Sustainable?

Finally, is this new movement sustainable? The absence of sustained grassroots organizing suggests that it is not. While some Black Churches have run parallel to the movement, and a few radical black theologians have joined it, #BlackLivesMatter does not seem to be ready to utilize fully the embedded and efficacious presence of black churches in every town and city where black folks are resident.[28] This is in turn linked to #BlackLivesMatter’s lack of firm connection to the base of ordinary African Americans. In contrast, the church-based Civil Rights activists could not fail to work with ordinary people, since without them they would not be able to have support to continue their efforts, and thus would become an even easier target for state violence to suppress their activism.

The African American base, that is, ordinary people in the community and on the street, do not know of intersectionality, genderqueer theory, or the like, and unfortunately for #BlackLivesMatter, it has not taken the time to do the mass political education necessary to convey these concepts and gain a following for them. Only on college campuses, mostly in elite institutions, are these discussions being had, mostly with students.[29] The overwhelming majority of U.S. blacks do not have a college degree. Why hasn’t #BlackLivesMatter made its underlying ideological narrative fully transparent and understandable to everyone, including the base that #BlackLivesMatter claims to speak for and defend?

Thus far, the state security apparatus has not targeted #BlackLivesMatter as a national security threat, unlike the earlier, mass-based Black movements that were targeted by the FBI for destruction as part of the COINTELPRO operation.[30] Could it be that the government knows something that #BlackLivesMatter doesn’t—that this new movement is ineffective, unlikely to obtain its objectives, and therefore is unlikely to have any substantive impact upon the existing order of things in American society?

Conclusion

In conclusion, #BlackLivesMatter has channeled the incandescent anger of many young black adults at perceived injustices related to the criminal justice system, and especially police abuses. But to paraphrase Scripture, #BlackLivesMatter has a form of righteousness, but denies the source thereof, [31] by rejecting the ethics and pragmatics of the indigenous social justice protest practices that Black Churches have engaged in and refined for centuries.[32] All such protest movements in the African American community, from the time of its enslavement in the 1600s, to the late 1960s, were theistically based in a Judeo-Christian ethical and cultural matrix. Because of its rejection of this element of black culture, #BlackLivesMatter is at risk of going where the other secular black protest movements of the late 60s and 70s arrived: that is, nowhere. It is a movie we have seen before, and we know how it ends.

Notes

1. The partial roll of these victims include: Amadou Diallo (1999), Sean Bell (2006), Oscar Grant (2009), Trayvon Martin (2012), Michael Brown, Jr. (2014), John Crawford III (2014), Ezell Ford (2014), Eric Garner (2014), Akai Gurley (2014), Dontre Hamilton (2014), Tamir Rice (2014), Freddie Gray (2015), Eric Harris (2015), Walter Scott (2015).

2. Nothing in this essay is meant to disparage the great physical and moral courage of the peaceful, non-violent demonstrators in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. Non-violent civic engagement by young adult African Americans is praiseworthy. They deserve a movement that has a durable social ethic, one that will last well beyond the current moment.

3. Sometimes the new movement uses black churches to hold its meetings and public protest actions. Sometimes the movement disrupts other public meetings at black churches. In October 2015 in Los Angeles, an act of violence occurred against the Rev. Kelvin Sauls, pastor of the Holman United Methodist Church, by Black Lives Matter activists who sought to disrupt a public forum there featuring Mayor Eric Garcetti regarding recent police shootings. In the aftermath, prominent black faith-based activists and clergy condemned Black Lives Matter for disrupting the event and creating a climate for violence, and demanded an apology, which was not given. See Black Lives Matter’s own reportage on this incident, in “These Savvy Women Have Made Black Lives Matter the most Crucial Left Wing Movement Today [sic],” blacklivesmatter.com, November 15, 2015, http://blacklivesmatter.com/these-savvy-women-have-made-black-lives-matter-the-most-crucial-left-wing-movement-today/.

4. See “Are We Postsecular?” Telos 167 (Summer 2014) for examples of this discussion.

5. “All significant concepts of the modern theory of the state are secularized theological concepts.” Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, trans. George Schwab (Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2006).

6. Alicia Garza, “A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement,” The Feminist Wire, October 7, 2014, http://www.thefeministwire.com/2014/10/blacklivesmatter-2/.

7. “Meet the Women Who Created #BlackLivesMatter,” blacklivesmatter.com, October 20, 2015, http://blacklivesmatter.com/meet-the-women-who-created-blacklivesmatter/.

8. Intersectionality was first coined by UCLA legal theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. At that time it was particularly situated within feminist and legal theory. Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 43 (July 1991): 1241–99.

9. Journalist Vanessa Vitiello Urqhart states, “The term genderqueer was originally coined in the 1990s to describe those who ‘queered’ gender by defying oppressive gender norms in the course of their binary-defying activism.” Vanessa Vitiello Urqhart, “What the Heck is Genderqueer?” Slate, March 24, 2015, http://www.slate.com/blogs/outward/2015/03/24/genderqueer_what_does_it_mean_and_where_does_it_come_from.html.

10. “This is Not a Moment, but a Movement,” blacklivesmatter.com, accessed January 19, 2016, http://blacklivesmatter.com/about/.

11. Christina Capecci, “‘Black Lives Matter’ Protesters Gather; Mall is Shut in Response,” New York Times, December 23, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/24/us/black-lives-matter-protesters-gather-mall-of-america-is-shut.html?_r=0.

12. Including Black Youth Project (BYP) 100, created by Prof. Cathy Cohen of the University of Chicago, the Dream Defenders, the Organization for Black Struggle, Hands Up United, and Millennial Activists United. “11 Major Misconceptions about the Black Lives Matter movement,” blacklivesmatter.com, October 1, 2015, http://blacklivesmatter.com/11-major-misconceptions-about-the-black-lives-matter-movement/. While the authors of this list are at pains to deny many of the concerns raised in this essay, their actual practices undercut the denials. However, as the Black Lives Matter network also states that it is not coextensive with the larger Black Lives Matter movement, it is not clear that these denials are truly determinative for Black Lives Matter as a whole. It should also be noted that the larger coalition is fragile, and some observers say that many other protest groups no longer ally themselves under the Black Lives Matter banner due in part to the inherent ideological differences identified here.

13. “Fox News & Right Wing Pundits,” blacklivesmatter.com, September 11, 2015, http://blacklivesmatter.com/fox-news-right-wing-pundits/.

14. An initial set of demands with many prefatory paragraphs was generated by a larger group of protest organizations including Black Lives Matter in response to President Barack Obama’s State of the Union Address in January 2015 that included most of these items. See “State of the Black Union,” #teamebony, Ebony, January 22, 2015, http://www.ebony.com/news-views/state-of-the-black-union-403#axzz3yigvBrqt. In July 2015, these came to greater public notice directly from Black Lives Matter. See “State of the Black Union—the Shadow of Crisis has NOT Passed,” blacklivesmatter.com, July 1, 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20150701011950/http://blacklivesmatter.com/state-of-the-black-union/. The current Black Lives Matter website as of January 30, 2016, does not contain this list of demands.

15. See co-founder Alicia Garza’s remarks in “Alicia Garza: Taking the Black Lives Matter Movement to Another Dimension,” blacklivesmatter.com, December 10, 2015, http://blacklivesmatter.com/alicia-garza-taking-black-lives-matter-to-another-dimension/.

16. An article at blacklivesmatter.com admits the lack of state violence against transgender black women, noting that “most of these women died at the hands of a presumably transphobic assailant or former intimate partner.” However, the article states that co-founder Alicia Garza “argues that the environment that allowed these women to be killed is the same that facilitates the longstanding pattern of unarmed black men being gunned down by law enforcement and vigilantes.” “Alicia Garza: Taking the Black Lives Matter Movement to Another Dimension,” blacklivesmatter.com, December 10, 2015, http://blacklivesmatter.com/alicia-garza-taking-black-lives-matter-to-another-dimension/. The article mentions that Ms. Garza is “a black queer woman (whose partner is trans).” The movement’s leaders have yet to elucidate the precise mechanisms that presumably create this deadly environment. Is it really White Privilege? Could it be that the root cause of this violence lies with local residents’ criminality, instead of law enforcement actions?

17. As the activists themselves state, “Black Lives Matter represents a move from a singular political organizing centered on racial justice to an intersectional agenda. Justice as imagined by its organizers is not only about ending anti-black racism. Visions of true justice must include freedom for black people who are queer, transgender, formerly or presently incarcerated, undocumented or facing any number of other challenges.” “Two Years Later, Black Lives Matter Faces Critiques, But It Won’t Be Stopped,” blacklivesmatter.com, accessed January 30, 2016, http://blacklivesmatter.com/two-years-later-black-lives-matter-faces-critiques-but-it-wont-be-stopped/.

18. “About #BlackLivesMatter,” blacklivesmatter.com, accessed January 30, 2016, http://blacklivesmatter.com/.

19. “About #BlackLivesMatter,” blacklivesmatter.com, accessed January 30, 2016, http://blacklivesmatter.com/.

20. Some representative texts discussing black women in the Civil Rights Movement include Aldon D. Morris, The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement (New York: The Free Press, 1984), and Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2003).

21. One of the movement’s founders, Patrisse Cullors, was quoted on its website stating that, “If you go into church in Los Angeles on a Sunday, the majority of the membership is 50 [years old] and up. . . . Younger black people are feeling less and less interested in the ideology of this church. . . . Many of the black people leading this movement are queer and trans, and have been kicked out by their churches.” “These Savvy Women Have Made Black Lives Matter the most Crucial Left Wing Movement Today [sic],” blacklivesmatter.com, November 15, 2015, http://blacklivesmatter.com/these-savvy-women-have-made-black-lives-matter-the-most-crucial-left-wing-movement-today/.

22. Galatians 3:28, New International Version, 1978.

23. The term “politics of respectability” was originally a positive and descriptive term, describing black Baptist women’s efforts to combat negative stereotypes of blacks by whites, and as a rational effort to ensure survival in the American South while advocating for black human rights. The term first appeared in Harvard historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham’s Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1993). Today, however, some black academics like the sociologist Patricia Hill Collins, in her Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism (New York: Routledge, 2004), have inverted its meaning to a pejorative one, specifically the idea of blacks attempting to appear “respectable” and avoid protest efforts in order to be deemed acceptable by white people. In the severe, deadly racism of the American South, and some places in the North as well, through the 1960s, the work of Civil Rights activists to show up in their “Sunday best” clothing and conduct themselves with a decorum that gave racists no legitimate grounds for attacking them, seems to be a rational, intelligent, and honorable tactic, especially when considering the use of social optics to control the narrative of black freedom in an age of television. The contemporary criticism of this tactic seems a classic case of the young dishonoring their elders.

24. Writer Jill Leovy notes that “the black homicide rate remained as much as ten times higher than the white rate in 1960 and 1970, and has been five to seven higher for most of the past thirty years.” Jill Leovy, Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America (New York: NY, Spiegel & Grau, 2015). Due to residential segregation and other factors, most murders are intra-racial, that is, committed against members of one’s own racial or ethnic group. However, the Bureau of Justice Statistics noted, “In 2008, the homicide victimization rate for blacks (19.6 homicides per 100,000) was 6 times higher than the rate for whites (3.3 homicides per 100,000).” Patterns and Trends: Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980–2008, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 236018, November 2011, p. 11, http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/htus8008.pdf.

25. See my further comments on this dialectic. Kenneth D. Johnson, “Legitimation Crisis in the ‘Hood: Will 2015 be like 1968?” TELOSscope, February 9, 2015, https://www.telospress.com/legitimation-crisis-in-the-hood-will-2015-be-like-1968/.

26. This movement’s lack of a theory of policing, and absence of a theory of black crime, contributes to this ethical deficit.

27. Others have noted this lack of concern also. See Oakland Tribune columnist Tammerlin Drummond’s article, “If Black Lives Matter then all black lives should matter,” Contra Costa Times, January 21, 2015, http://www.contracostatimes.com/breaking-news/ci_27367063/drummond-if-black-lives-matter-then-all-black.

28. This is linked to the ideological exclusion of the churches. The Movement for Black Lives conference in Cleveland, Ohio in July 2015 had a list of over 115 seminars. Only one discussed the role of Black Churches in the new movement. There was another called “Healing from Black Church Trauma in the Quest for Black Liberation.” There were many more seminars on mindfulness and Yoga. See movementforblacklives.org, accessed January 19, 2016, http://movementforblacklives.org/schedule/.

29. Some of the leaders of local Black Lives Matters are quite élite, indeed. See the description of some of their backgrounds at “These Savvy Women Have Made Black Lives Matter the most Crucial Left Wing Movement Today [sic],” blacklivesmatter.com, November 15, 2015, http://blacklivesmatter.com/these-savvy-women-have-made-black-lives-matter-the-most-crucial-left-wing-movement-today/.

30. However, private security firms are alleged to have been hired by local police forces to monitor the activities of Black Lives Matter protestors, presumably for intelligence gathering to respond to non-violent protests and possible subsequent rioting. TakePart Media’s PIVOT TV aired in January 2016 an online documentary alleging these steps are being taken. See “Truth and Power: #BLACKLIVESMATTER,” www.takepart.com, January 22, 2016, http://www.takepart.com/pivot/truth-and-power/episodes.

31. “Having a form of godliness, but denying the power thereof: from such turn away.” 2 Timothy 3:5, King James Version.

32. See the Princeton scholar Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: the ‘Invisible Institution’ in the Antebellum South, updated ed. (New York: Oxford UP, 2004) for a discussion of the underground Black Church under slavery. Also, see the late Eugene D. Genovese, Roll Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Random House, 1974) for an excellent review of the role of religion, and resistance, in the lives of enslaved black persons.

© 2016 Kenneth D. Johnson