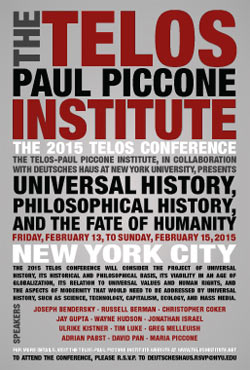

The following paper was presented at the 2015 Telos Conference, held on February 13–15, 2015, in New York City. For additional details about the conference, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

Archaeologists have found the oldest known example of complex intergenerational cooperation at Göbekli Tepe in southern Turkey. Thirty miles away, just across the Syrian border, is the latest flashpoint of a complex intergenerational conflict—what President Obama calls the “barbarism” of the Islamic State.[1] What does the world’s oldest civilization have to do with the world’s newest barbarians? Both show the fundamental role of religion in organizing human societies.

Archaeologists have found the oldest known example of complex intergenerational cooperation at Göbekli Tepe in southern Turkey. Thirty miles away, just across the Syrian border, is the latest flashpoint of a complex intergenerational conflict—what President Obama calls the “barbarism” of the Islamic State.[1] What does the world’s oldest civilization have to do with the world’s newest barbarians? Both show the fundamental role of religion in organizing human societies.

Viewing civilization as the product of religion bucks a long academic tradition. A consensus holds that human culture is an adaptive response to the environment. Ecological factors shape the economic base of society, molding civilizations in different ways. Thus, in the “Neolithic Revolution” hypothesis of V. Gordon Childe, civilization originated when the global climate warmed some 12,000 years ago, such that human beings could cultivate grains in fertile river valleys (Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and China). This was the economic base upon which a civilizational superstructure—hierarchies, regimes, and religion itself—was built.

Göbekli Tepe shattered this framework when the German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt published his findings in the early 2000s. At the site, nomadic hunter-gatherers built monuments and fed specialized workers. Two hundred T-shaped pillars, some twenty feet tall and weighing as many as twenty tons, are arranged in circular patterns and decorated with ornate animal carvings. Why organize a city where nobody lived? Schmidt proposes that Göbekli Tepe was a “cathedral on a hill.”[2] Schmidt’s claim—”First came the temple, then the city”—changes our basic picture of the first civilizations, and of our own.[3]

Civilizational analysis and comparison, a method one might associate with Arnold Toynbee or Oswald Spengler, is making a comeback as a sociological alternative to universal history. Civilisation was an eighteenth-century French neologism that replaced the earlier policie.[4] It is felicitous if contemporary English ears hear “police,” because this paper will focus upon civilization through the lens of gouvernementalité—Foucault’s more recent French neologism. This précis of that longer paper introduces a concept of civilization as an ideal compatibility of an actual network of disciplinary institutions.

Civilization involves a widespread belief in ideas, and is actualized through effective discipline. Nietzsche called this ideal basis of Roman civilization, for example, a Begriffsdome or “concept-cathedral” constructed “upon a moving foundation, as it were, on flowing water.”[5] In the less poetical terms of modern sociology, civilization is a social imaginary, broadly including the “images, stories, and legends” shared by large groups of people.[6] The temple typically comes before the city because disciplining a population with a social imaginary drastically lowers the costs of extending and maintaining power.

Intellectual historians of modernity typically show how the secular West was “imagined” in a certain constellation of late medieval theological ideas. Modern disciplinary institutions—public schools, secular universities, prisons, hospitals—are very different from the network of disciplinary regimes in the Middle Ages, over which the Catholic Church at least theoretically supervened. But it is too simplistic to presume that fatigued survivors of the Wars of Religion invented the conceptual tools to build a secular, liberal civilization in just a few generations. Instead, intellectual historians from Hans Blumenberg to Louis Dupré have shown how late medieval Franciscan theologies informed the modern “social imaginary”—some combination of Scotism, conciliarism, nominalism, and voluntarism. Basically (bracketing all the interesting questions of intellectual historians) Franciscans argued that radical poverty was commanded of them by the will of God. Thus, they argued property was not a constituent feature of some natural law of creation. The Franciscans’ theological emphasis on the liberty of the divine will, rather than upon the discernable natural laws of creation, cleared the topos of modernity. But this is a vast field of inquiry carried out at a high level of abstraction.

Beyond the intellectual history of modernity, one needs to ask how these ideas are operationalized in the world, requiring a methodological turn towards institutions. Where were these ideas taught, and what were these schools like? Franciscans may have disciplined radical friars, but it was the Calvinists who first disciplined radical citizens. This essay will look at a case study where scholastic discipline paved the way for an “alternative modernity” or a radically new conceptions of civilization: the Calvinist schoolteachers of the early modern Netherlands, and end with some thoughts about how this historical case sheds light on radical Islamism today.

John Calvin combined a challenge to medieval kingship with a proscription for a new kind of religious discipline. Calvin’s 1536 Institutes of the Christian Religion is prefaced with a warning to the King of France, and ends with an ominous warning that sometimes God raises up “open avengers”—”Let princes hear and be afraid.”[7] Calvin argued that political resistance was necessary for others’ salvations, and the Calvinist tradition authorized the first Christian regicides, in theory and practice.[8] Calvin prepared the way with a vision of normalizing discipline rather than punishment; his favorite metaphor was the bridle-and-spur, which instilled self-discipline in subjects.[9] This self-discipline prepared the way for what Michael Walzer’s classic 1965 study called the “revolution of the saints,” which was nothing less than a “theoretical justification for independent political action. . . . What Calvinists said of the saint, other men would later say of the citizen.”[10]

Philip S. Gorski’s The Disciplinary Revolution presents the Netherlands as a case study of Calvinist religious discipline. Like Calvinists elsewhere in Europe, the Dutch saw schools as the primary instruments of social discipline, and instituted a nascent public education system. The Dutch government was “tasked to see that the schoolmasters subscribe to the Confession of Faith, submit to the discipline, and also instruct the youth in the Catechism.”[11] As a result, the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic was an anomaly of order, and, despite a lack of a police force, had the highest rates of per capita military service and taxation in Europe. The efficiency of the Dutch regime allowed them to punch well above their weight, holding off the world empire of Catholic Spain. Through this religious discipline, a new world order was emerging in the Thirty Years’ War—our own.

Today there are still transnational networks of radical believers, textual literalists willing to commit acts of violence prohibited by international law. If the prospect of a caliphate today, whether after the fashion of Al Qaeda or the Islamic State, muscling its way into our world system seems remote, one should consider the mid-sixteenth-century Calvinist outposts in the wars of religion, Calvin’s Geneva or Knox’s Scotland. One might also consider the Taliban in Afghanistan, which emerged from the religious discipline of Pakistani madrasas to wield more infrastructural power than the Soviet Union or NATO was able to do.

The lesson of Göbekli Tepe is that civilization is cheaper than we once thought. Even without a substantive economic base, or the perfect environmental conditions, a foundationless religious idea is enough to launch a civilizational project. Modern nomads, from sixteenth-century Calvinist radicals with their pamphlets, to twenty-first-century militant Islamists on YouTube and social media, have done the same. Civilizations emerge in effective discipline, which we see in the Reformed consistories’ emphasis on compulsory schooling and the emphasis on new strict school curricula by the Islamic State.

What we see on the news from Syria and Iraq is neither anomalous nor retrograde in any “grand scheme.” To the contrary, it seems possible that Western political tendencies to either underestimate radical Islam (usually on the Left) or essentialize it as Other (usually on the Right) might be related to an inability to understand the religious origins of Western civilization.

Notes

1. Ben Wolfgang, “Obama condemns ISIL’s ‘barbaric’ slaying of David Haines,” Washington Times, September 14, 2014.

2. Joris Peters and Klaus Schmidt, “Animals in the symbolic world of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, South-Eastern Turkey: A Preliminary Assessment,” Anthropozoologica 39.1 (2004): 179–218; here, p. 214.

3. Klaus Schmidt, “‘Zuerst kam der Tempel, dann die Stadt’: Vorläufiger Bericht zu den Grabungen am Göbekli Tepe und am Gürcütepe 1995–1999,” Istanbuler Mitteilungen 50 (2000): pp. 5–41. See also C. J. C. Pickstock, “The Ritual Birth of Sense,” Telos 162 (Spring 2013): 29–55.

4. Krishan Kumar, “The Return of Civilization—and of Arnold Toynbee?” Comparative Studies in Society and History 56:4 (2014): 815–43; here, pp. 817 and 821.

5. Friedrich Nietzsche, “Über Wahrheit und Lüge im außermoralischen Sinne” (1874).

6. Charles Taylor, Modern Social Imaginaries (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), p. 23.

7. John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 2 vols., ed. John T. McNeill (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006), cf. ICR. IV.xx.30. p. 1517.; ICR. 1v.xx.31. p. 1518.

8. Cf. “Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos” (1579), in G. H. Sabine, A History of Political Theory, ed. Thomas Landon Thorson, (Chicago: Dryden Press, 1973), p. 352.

9. ICR. IV.xii.2–3. pp. 1230–31.; ICR. IV.xii.9–10. pp. 1237–38.

10. Michael Walzer, The Revolution of the Saints: A Study in the Origin of Radical Politics (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965), p. 2.

11. A. C. Duke, Gillan Lewis, and Andrew Pettegree, Calvinism in Europe, 1640–1610 (Manchester University Press, 1992), p. 172.