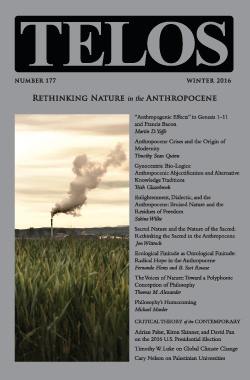

In addition to its main focus on nature and the Anthropocene, Telos 177 (Winter 2016) features a special section of topical writing, introduced here by Russell A. Berman, that continues our ongoing commitment to setting forth a critical theory of the contemporary. Telos 177 is now available for purchase in our store.

After a rancorous and ugly presidential campaign, in which vitriol and name-calling replaced discussion and policy, one moment stands out for its dignity: President Obama’s grace and generosity when he welcomed the president-elect to the White House. Above the fray and with a Lincolnian refusal of malice, he modeled a possibility of reconciliation and healing, as if citizens might genuinely respect each other, despite profound differences. That utopia will likely remain elusive, but the president’s bearing provides a lesson in civic virtue. Democracy can be coarse. He showed how it can be better. That legacy will be important.

After a rancorous and ugly presidential campaign, in which vitriol and name-calling replaced discussion and policy, one moment stands out for its dignity: President Obama’s grace and generosity when he welcomed the president-elect to the White House. Above the fray and with a Lincolnian refusal of malice, he modeled a possibility of reconciliation and healing, as if citizens might genuinely respect each other, despite profound differences. That utopia will likely remain elusive, but the president’s bearing provides a lesson in civic virtue. Democracy can be coarse. He showed how it can be better. That legacy will be important.

Donald Trump not only avoided the landslide defeat that many had predicted but was able to secure a clear electoral college majority and nearly half the popular vote. This result came as such a surprise because the political class, the press, the pollsters, and the pros had succumbed to their own wishful thinking. This outcome was not supposed to happen because it had not been foreseen, as if reality has an obligation to conform to expectations. Such a failure of political prediction—analogous to the failure of economic prediction in 2008—should lead, by all rights, to professional soul-searching. Instead, the commentariat in the leading newspapers is vigorously protecting its viewpoints, while preferring to denounce the voters for their misbehavior: the electorate was wrong, not the liberal opinion-makers and certainly not the defeated politicians. Blame the people. One recalls Bertolt Brecht’s poem “The Solution,” written in the aftermath of the crushed workers’ uprising against the Communist East German regime in June 1953, in which he suggests, with bitter irony, that the government should dissolve the people and elect a new one.

As far as the ballot box results go, both Clinton and Trump underperformed their respective predecessors, garnering fewer votes than did Obama and Romney respectively in 2012. This was a campaign between two candidates with high negatives and for many voters a question of whom one disliked less. A choice between such disliked candidates necessarily poisoned the process. It was also the year of an insurgency against the party hierarchies, no longer viewed as effective vehicles for the political sentiments of their bases. That anti-establishment dynamic builds on deep history, a matter of anarchist, spontaneist, or “Luxemburgian” refusals of the dictates of party leaders and central committees (see the Brecht reference above). Yet this revolt played out in dramatically asymmetrical ways. Trump crushed the Republican leadership, while the Democratic National Committee defeated Sanders: a successful revolution versus a failed one. Might Sanders have fared better than Clinton? The bloodletting among Democrats will probably go on for a while, and the future of the party is unclear. It could become as bizarre as the British Labor Party or as ineffective as the French Socialists—there are no good models for center-left parties these days.

The Clinton campaign’s choice to focus on Trump’s personality rather than on policies did not pay off. The pursuit of his identity-political vulnerabilities, his or his supporters’ notoriously “deplorable” character, was not as productive as hammering on social and foreign policy substance could have been. For all the talk of the promise of her breaking the glass ceiling and Trump’s misbehavior toward women, her percentage of the female vote (54%) was less than Obama’s in 2012 (55%), while Trump’s fraction of women voters (42%) was only slightly below Romney’s (44%). All the attention to Trump as sexist personality evidently did not generate votes. Moreover, despite Trump’s language, which even Paul Ryan characterized as textbook racism, the Republican fraction of the minority vote in 2016 was marginally greater than in 2012. For African Americans it rose from 6% to 8%, for Asian Americans from 26% to 29%, and for Hispanics from 27% to 29%. Evidently the denunciations of Trump as racist did not reduce his percentage of support among minority voters. Race and racism alone do not explain this election. We need better analyses.

Trump has rewritten the playbook on how to conduct a presidential campaign in the twenty-first century. He did not rely on the army of professional political advisors, traditional fund-raising, or standard get-out-the-vote efforts. In addition, the Clinton team made strategic errors, for example disregarding even Bill Clinton’s advice to pay more attention to the Rust Belt, just as, in a similar vein, Hillary chose to turn down an opportunity to deliver a major address at Notre Dame, allegedly discounting the need to pursue Catholic voters.

Beyond these campaign errors, one has to consider policy constellations that just do not fit the standard journalistic narratives that dominated the coverage. Most remarkably, this was the first election in generations in which the Democratic candidate, viewed by many as the hawk in the race, ran to the right of Republicans on foreign policy. Whether Trump attracted much of the anti-war left is unlikely, but part of that constituency may have been reluctant to vote for Clinton, perceived as inclined toward a more aggressive foreign policy posture. At times, Trump was therefore attacked as an “isolationist,” a term that conjures up archaic right-wing legacies, but in practice it significantly overlaps with a left-wing anti-imperialism and, more importantly, with a genuine and legitimate war-weariness in the population, especially in those communities that bear the burden of the wounds of war and bury the dead. Foreign policy is hardly the sole factor driving presidential elections, but it would not be wrong to say that this time, it was the candidate of détente who won. Yet this détente, Trump’s version of a reset with Russia, may be a risky chessboard move to induce the Europeans to pick up more of the costs of their own defense.

It could turn out that a less interventionist foreign policy is not the only traditional Democratic position that Trump was able to occupy: infrastructure investment comes to mind, as do protection of Social Security and in general a backing off from fiscal hawkishness (and Trump’s willingness to spend may cause him problems with the Republican Congress). The election has reshuffled the card deck.

In this issue’s Critical Theory of the Contemporary, three Telos editors offer their distinct responses on the election outcome. Adrian Pabst addresses the Clinton defeat by taking a broader view of decades of Democratic Party reorientation toward a professional new class (a topic familiar to long-term readers of this journal). His argument bears some resemblance to Thomas Frank’s recent commentaries and other discussions on the left, except that Pabst’s implicit solutions run more along the lines of mutuality, subsidiarity, and community rather than the template progressive preference for more centralization and expanded bureaucracy. He proceeds to characterize Trump’s combination of “nationalist-libertarian ideas with a preference for populist-authoritarian leadership,” and he places this profile firmly in a longer American history. Ultimately Pabst gauges Trump as the businessman out to make the better deal, including a prospective coming-to-terms with Vladimir Putin. After seeing Moscow snooker Washington in the tragically unproductive Syria negotiations, it is worth considering whether some business acumen might produce better results when facing a tough competitor.

Kiron Skinner explores whether we are witnessing a sea change in American politics. While it is true that Trump succeeded in mobilizing white working-class voters, Skinner also shows his significant impact on the African-American vote once he began to address the condition of black America directly. During the summer, Trump was polling at zero percent of the black vote, but in his August 22 speech in Akron he addressed head-on the economic plight of the black community. It has born the brunt of the Great Recession, with higher poverty and unemployment rates. In Skinner’s words: “African Americans have not fared well under a Democratic president who is also African American. Nor have millions of them seen anything close to prosperity under the urban Democratic machines that have been firmly entrenched for decades and decades.” Once Trump took these issues on, he was able to climb to 8 percent of the black vote in November, better than Romney in 2012. “The fact that thousands of black voters sifted through the noise about Trump being a racist and were persuaded by his message suggests that they could become a numerically significant component of a potentially powerful coalition of those for whom the American Dream appears too distant to even consider. If Trump delivers jobs and economic growth to Americans, this coalition may emerge and millions of African Americans may return to the party of Lincoln.”

David Pan puts the election into a larger global and theoretical framework. He argues that liberalism is in retreat around the world, both the liberalism of individual rights and the liberalism of the free market and free trade. He describes this shift from the primacy of universalist principles, increasingly challenged by a willingness to assert national interests more emphatically. Such a reversal has, he argues, particularly dramatic significance for the United States, the very constitution of which involves a commitment to liberal freedoms and a conceptual universalism. A turn to an ethnic particularism would run against the grain of American identity and undercut its standing in the world. “The United States would contribute to turning international politics into a zero-sum game, each nation protecting its own interests in a struggle against other nations. The result could be a fragmentation of the world into separate spheres of hegemony, nuclear proliferation, and the collapse of global climate change agreements—not to even consider worst-case scenarios.” Yet through a reflection on the history of political theory, Pan proceeds to reconstruct liberalism, less an expression of reason per se—surely a hubristic overstatement—than as one particular tradition that remains a fertile ground for free societies. The United States retains a distinct capacity to safeguard and disseminate that tradition, “promoting liberal principles all over the world, not as a form of hegemonic self-interest, but as an expression of the commitment to justice and freedom for all.” In the wake of the election, Pan detects an opportunity to surpass the fragmentation of the identity-political era and to rebuild a coherent political community based on liberal and inclusive principles instead of on group grievances. “If the Trump administration is able to find its way to defend these principles at home and abroad, essentially adhering to a more traditional Republican agenda, it will be a welcome reaffirmation of the strength of America’s liberal traditions.”

One of the more disappointing aspects of this bizarre campaign was the absence of sustained discussion about climate change. As Telos editor Tim Luke points out, “not a single question about climate change was raised at any of the three nationally televised debates between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump.” The moderators, distinguished journalists all, had plenty of time for salacious incidents or personal scandals but none for the fate of the earth. Yet four days before the election, the Paris Climate Change Accords were formalized at the 22nd “Conference of the Parties” (COP) held in Marrakesh. American participation took place only via executive order, and is therefore revocable. Luke demonstrates the interplay of science and politics in global environmental management dynamics. As much as the future of the earth is at stake, national interests never disappear. While this should come as no surprise, it potentially amplifies the effects of a “post-globalist” politics evident in other spheres, such as trade and immigration. Moreover Luke shows how “climatological nationalism” shifts pollution-producing industrialization into the global South, while net global pollution continues: “transnational corporate networks have rapidly decamped from the deindustrializing zones in the pollutant leader countries, like the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, or France, while they quickly dispersed into the newly industrialized regions in one-time pollution laggards . . . . This shift does stimulate new production centers. Still, their output mostly has benefited pollution leaders with cheaper goods, less pollution, and new innovations, while creating more economic precarity, environmental degradation, and commercial fragility for many one-time pollution laggard countries.” For the future, then, the challenge is not only the skepticism regarding climate change in the new administration but also the structural flaws in the climate accords regime itself. Relocating greenhouse gas production from the Rust Belt to Brazil may generate good feeling in the activist community (if not among the unemployed workers in Detroit), but it does not reduce net environmental degradation.

Finally this section includes an extensive report by Cary Nelson on conditions in Palestinian universities, in particular how the political regimes in the West Bank and Gaza, the Palestinian Authority and Hamas, systematically deny scholars academic freedom. Through detailed descriptions of several cases, involving a range of political orientations, Nelson documents the intense pressures faced by individual professors and students as well. Mohammed Dajani, a faculty member at Al-Quds University, took students on a trip to Auschwitz in an effort to acquaint his students with the reality of the Holocaust. For this he not only faced denunciations and official distancing by the university. His office was ransacked, and an assassination attempt followed. Another victim, Abdul Sarrat Qassem, a political scientist at Nablus and a columnist for Al Jazeera, was arrested for criticisms of the PA: faculty clearly do not have freedom to express dissenting political views in Palestinian universities. The Islamic University of Gaza is especially characterized by an imposed political uniformity, a monolith of ideology. These and additional examples would deserve, on their own merits, harsh criticism from scholars abroad. Yet, with the exception of this report, they have received scant attention. While the academic left in the United States and Europe has focused its condemnations on Israel and called for an academic boycott, it has remained consistently blind to infringements on academic freedom within Palestinian universities. Professional associations such as the American Studies Association and the American Anthropological Association have been harshly critical of Israel. Their silence on internal Palestinian attacks on academic freedom can only be taken as endorsement of these repressive practices. Palestinians cannot count on these Western academics to protest unless there is an opportunity to attack Israel. Otherwise denials of academic freedom are perfectly acceptable to the progressive scholars who lead our professional associations. This is the Palestinian shame.