By Johanna K. Schenner · Wednesday, September 17, 2014  In “Franz Kafka in Eastern Europe,” Antonin J. Liehm addresses the impact of Kafka on both the communist literary sphere and the regime following the May 1963 Liblice Conference, an international symposium dealing with Kafka’s life and work. At first glance, this symposium does not appear to be remarkable: Kafka, known for such works as “The Metamorphosis” (1915) and “The Castle” (1926), was born in Prague in 1883, and he worked there as a lawyer before dying in 1924 in the sanatorium at Kierling, located in Klosterneuburg, Austria. Nonetheless, the symposium revealed that the socialist regimes were less totalitarian than supposed, if only for a short time, and it also attributed to Kafka a significant role in the beginning of cultural democratization, which then spread to other spheres. In “Franz Kafka in Eastern Europe,” Antonin J. Liehm addresses the impact of Kafka on both the communist literary sphere and the regime following the May 1963 Liblice Conference, an international symposium dealing with Kafka’s life and work. At first glance, this symposium does not appear to be remarkable: Kafka, known for such works as “The Metamorphosis” (1915) and “The Castle” (1926), was born in Prague in 1883, and he worked there as a lawyer before dying in 1924 in the sanatorium at Kierling, located in Klosterneuburg, Austria. Nonetheless, the symposium revealed that the socialist regimes were less totalitarian than supposed, if only for a short time, and it also attributed to Kafka a significant role in the beginning of cultural democratization, which then spread to other spheres.

Continue reading →

By Jacob Dreyer · Thursday, May 29, 2014  In China as in the Soviet Union, it seemed particularly cruel to “political” prisoners that thieves, rapists, and murderers should be placed higher in the camp hierarchy than they were. From the perspective of the CCP, this often touched on the point of class origins, for of course the intellectual class often emerged from the urban bourgeoisie, whereas the common criminals come from the dodgy, poor neighborhoods or, in their rural equivalent, poor, burned-out villages. However, what the victorious revolutionaries sought to achieve was the laborious process of lifting the world off of its axle and inverting it, like a gigantic bureau drawer; of course all sorts of things fall out, and if they are delicate, shatter. The intellectual class was, and is, that class which had already begun lifting themselves out of the material world, on their own terms, with thought. For those authorities who wish to arrange a collective transfer of all resources and persons from the old world into a still unimaginable new one, this individualistic secession from the world is a most dangerous form of treason, in comparison to which the rapes, knifings, stolen bread, and liquor of the underclass are all too easy to forgive. For the latter are simply operating the system in their own disadvantaged way, with the same objectives, finally, as the capitalists and lords, whereas the thinkers seek to float away entirely. It is for this reason that in the camps, the political prisons were considered “external contradictions,” the criminals, “internal contradictions.” In China as in the Soviet Union, it seemed particularly cruel to “political” prisoners that thieves, rapists, and murderers should be placed higher in the camp hierarchy than they were. From the perspective of the CCP, this often touched on the point of class origins, for of course the intellectual class often emerged from the urban bourgeoisie, whereas the common criminals come from the dodgy, poor neighborhoods or, in their rural equivalent, poor, burned-out villages. However, what the victorious revolutionaries sought to achieve was the laborious process of lifting the world off of its axle and inverting it, like a gigantic bureau drawer; of course all sorts of things fall out, and if they are delicate, shatter. The intellectual class was, and is, that class which had already begun lifting themselves out of the material world, on their own terms, with thought. For those authorities who wish to arrange a collective transfer of all resources and persons from the old world into a still unimaginable new one, this individualistic secession from the world is a most dangerous form of treason, in comparison to which the rapes, knifings, stolen bread, and liquor of the underclass are all too easy to forgive. For the latter are simply operating the system in their own disadvantaged way, with the same objectives, finally, as the capitalists and lords, whereas the thinkers seek to float away entirely. It is for this reason that in the camps, the political prisons were considered “external contradictions,” the criminals, “internal contradictions.”

Continue reading →

By Beau Mullen · Tuesday, December 10, 2013 As an occasional feature on TELOSscope, we highlight a past Telos article whose critical insights continue to illuminate our thinking and challenge our assumptions. Today, Beau Mullen looks at Norman Naimark’s “Totalitarian States and the History of Genocide” from Telos 136 (Fall 2006).

The twentieth century was witness to no shortage of political violence and mass death perpetrated by the state. The two most well-known genocides of the century—those that occurred under the rule of Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union—did not occur because the state broke down and lawlessness prevailed. Quite the contrary: both regimes had complete control over their citizenry, and the apparatus of government was used to make the butchery as efficient and as inescapable as possible. Both regimes were characterized by extreme violence and terror, key elements of the totalitarian system as defined by Hannah Arendt, so it seems only logical that totalitarianism increases the potential for genocide. The twentieth century was witness to no shortage of political violence and mass death perpetrated by the state. The two most well-known genocides of the century—those that occurred under the rule of Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union—did not occur because the state broke down and lawlessness prevailed. Quite the contrary: both regimes had complete control over their citizenry, and the apparatus of government was used to make the butchery as efficient and as inescapable as possible. Both regimes were characterized by extreme violence and terror, key elements of the totalitarian system as defined by Hannah Arendt, so it seems only logical that totalitarianism increases the potential for genocide.

Continue reading →

By Danilo Breschi · Thursday, July 25, 2013 Danilo Breschi’s “From Politics to Lifestyle and/or Anti-Politics: Political Culture and the Sense for the State in Post-Communist Italy” appears in Telos 163 (Summer 2013). Read the full version online at the Telos Online website, or purchase a print copy of the issue in our store.

In Italy, the transition from communism to post-communism, from the PCI to today’s Democratic Party, has been determined and strongly influenced not only by the collapse of ideologies and by the changes in the international political scene after 1989, but also by the profound changes that have invested the customs, lifestyles, and collective mentality from the end of the 1960s and, ever more rapidly, from the 1970s. Mass individualism and consumer society are the factors that more than others have undermined the myth of the anthropological “diversity” and the claim to moral superiority cultivated for decades by the Italian communists. Moreover, they help explain the passage of many of them from the utopia revolutionary and the dream of a “new world” to the liberal-bourgeois radicalism that seems to characterize today’s Italian left. Is there anything left of the communist tradition in today’s Italian political and cultural scenario? There is probably one attitude shared by many Communist militants but that belongs to the entire Italian political tradition, i.e., the deeply rooted aversion to public institutions and a poor sense of the state as embodying the rule of law. The greatest and most negative legacy of the long hegemony, on the left, of a communist party narrowly loyal to the Soviet Union was and still is the lack of legitimacy of the state and its institutions. The Soviet experiment having failed, there remains a populist cultural capital that has passed on to the Lega Nord in the 1990s and that has recently migrated to the Five Stars Movement of Beppe Grillo. In Italy, the transition from communism to post-communism, from the PCI to today’s Democratic Party, has been determined and strongly influenced not only by the collapse of ideologies and by the changes in the international political scene after 1989, but also by the profound changes that have invested the customs, lifestyles, and collective mentality from the end of the 1960s and, ever more rapidly, from the 1970s. Mass individualism and consumer society are the factors that more than others have undermined the myth of the anthropological “diversity” and the claim to moral superiority cultivated for decades by the Italian communists. Moreover, they help explain the passage of many of them from the utopia revolutionary and the dream of a “new world” to the liberal-bourgeois radicalism that seems to characterize today’s Italian left. Is there anything left of the communist tradition in today’s Italian political and cultural scenario? There is probably one attitude shared by many Communist militants but that belongs to the entire Italian political tradition, i.e., the deeply rooted aversion to public institutions and a poor sense of the state as embodying the rule of law. The greatest and most negative legacy of the long hegemony, on the left, of a communist party narrowly loyal to the Soviet Union was and still is the lack of legitimacy of the state and its institutions. The Soviet experiment having failed, there remains a populist cultural capital that has passed on to the Lega Nord in the 1990s and that has recently migrated to the Five Stars Movement of Beppe Grillo.

Continue reading →

By Yonathan Listik · Tuesday, November 27, 2012 As an occasional feature on TELOSscope, we highlight a past Telos article whose critical insights continue to illuminate our thinking and challenge our assumptions. Today, Yonathan Listik looks at Georg Lukács’s “The Old Culture and the New Culture” from Telos 5 (Spring 1970).

It would be simplistic to argue that behind the Marxist critiques of capitalist society there was only an objective intention simply to improve its effectiveness and avoid the political complications found in capitalist society. Despite its strict scientific tone, Marxism still carries a heavily moral intention. This is what Georg Lukács comes to argue in this essay on culture. In his analysis of capitalist cultural structure and its many differences from capitalist reality, Lukács points to what he regards as the ultimate goal behind communism: a new cultural order. It would be simplistic to argue that behind the Marxist critiques of capitalist society there was only an objective intention simply to improve its effectiveness and avoid the political complications found in capitalist society. Despite its strict scientific tone, Marxism still carries a heavily moral intention. This is what Georg Lukács comes to argue in this essay on culture. In his analysis of capitalist cultural structure and its many differences from capitalist reality, Lukács points to what he regards as the ultimate goal behind communism: a new cultural order.

Continue reading →

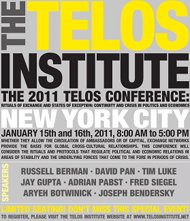

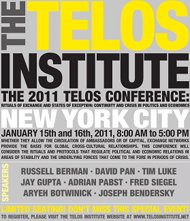

By Álvaro Cúria · Thursday, March 17, 2011 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2011 Telos Conference, “Rituals of Exchange and States of Exception: Continuity and Crisis in Politics and Economics.”

This work results from the development of a Master’s thesis for the Master in Communication Sciences, at the Faculty of Arts of the University of Porto. My thesis was under the theme “The Communication of Communist Ideology after the Fall of the Berlin Wall: Limitations, Disruptions and Opportunities. The Portuguese Case: The Image of the Portuguese Communist Party in the 21st century.” Our main question is whether communism is recognized as being valid today. The thesis is based on a theoretical and methodological approach on the identity, historical background, and validity of certain vectors related to communist ideology in today’s society. The object of the work is the communist ideology, mainly the European communism and the Portuguese Communist Party. A second part of this research work is complemented with a study of the party’s image made after conducting a survey of 600 students from the University of Porto. This work results from the development of a Master’s thesis for the Master in Communication Sciences, at the Faculty of Arts of the University of Porto. My thesis was under the theme “The Communication of Communist Ideology after the Fall of the Berlin Wall: Limitations, Disruptions and Opportunities. The Portuguese Case: The Image of the Portuguese Communist Party in the 21st century.” Our main question is whether communism is recognized as being valid today. The thesis is based on a theoretical and methodological approach on the identity, historical background, and validity of certain vectors related to communist ideology in today’s society. The object of the work is the communist ideology, mainly the European communism and the Portuguese Communist Party. A second part of this research work is complemented with a study of the party’s image made after conducting a survey of 600 students from the University of Porto.

Continue reading →

|

|

In “Franz Kafka in Eastern Europe,” Antonin J. Liehm addresses the impact of Kafka on both the communist literary sphere and the regime following the May 1963 Liblice Conference, an international symposium dealing with Kafka’s life and work. At first glance, this symposium does not appear to be remarkable: Kafka, known for such works as “The Metamorphosis” (1915) and “The Castle” (1926), was born in Prague in 1883, and he worked there as a lawyer before dying in 1924 in the sanatorium at Kierling, located in Klosterneuburg, Austria. Nonetheless, the symposium revealed that the socialist regimes were less totalitarian than supposed, if only for a short time, and it also attributed to Kafka a significant role in the beginning of cultural democratization, which then spread to other spheres.

In “Franz Kafka in Eastern Europe,” Antonin J. Liehm addresses the impact of Kafka on both the communist literary sphere and the regime following the May 1963 Liblice Conference, an international symposium dealing with Kafka’s life and work. At first glance, this symposium does not appear to be remarkable: Kafka, known for such works as “The Metamorphosis” (1915) and “The Castle” (1926), was born in Prague in 1883, and he worked there as a lawyer before dying in 1924 in the sanatorium at Kierling, located in Klosterneuburg, Austria. Nonetheless, the symposium revealed that the socialist regimes were less totalitarian than supposed, if only for a short time, and it also attributed to Kafka a significant role in the beginning of cultural democratization, which then spread to other spheres.  In China as in the Soviet Union, it seemed particularly cruel to “political” prisoners that thieves, rapists, and murderers should be placed higher in the camp hierarchy than they were. From the perspective of the CCP, this often touched on the point of class origins, for of course the intellectual class often emerged from the urban bourgeoisie, whereas the common criminals come from the dodgy, poor neighborhoods or, in their rural equivalent, poor, burned-out villages. However, what the victorious revolutionaries sought to achieve was the laborious process of lifting the world off of its axle and inverting it, like a gigantic bureau drawer; of course all sorts of things fall out, and if they are delicate, shatter. The intellectual class was, and is, that class which had already begun lifting themselves out of the material world, on their own terms, with thought. For those authorities who wish to arrange a collective transfer of all resources and persons from the old world into a still unimaginable new one, this individualistic secession from the world is a most dangerous form of treason, in comparison to which the rapes, knifings, stolen bread, and liquor of the underclass are all too easy to forgive. For the latter are simply operating the system in their own disadvantaged way, with the same objectives, finally, as the capitalists and lords, whereas the thinkers seek to float away entirely. It is for this reason that in the camps, the political prisons were considered “external contradictions,” the criminals, “internal contradictions.”

In China as in the Soviet Union, it seemed particularly cruel to “political” prisoners that thieves, rapists, and murderers should be placed higher in the camp hierarchy than they were. From the perspective of the CCP, this often touched on the point of class origins, for of course the intellectual class often emerged from the urban bourgeoisie, whereas the common criminals come from the dodgy, poor neighborhoods or, in their rural equivalent, poor, burned-out villages. However, what the victorious revolutionaries sought to achieve was the laborious process of lifting the world off of its axle and inverting it, like a gigantic bureau drawer; of course all sorts of things fall out, and if they are delicate, shatter. The intellectual class was, and is, that class which had already begun lifting themselves out of the material world, on their own terms, with thought. For those authorities who wish to arrange a collective transfer of all resources and persons from the old world into a still unimaginable new one, this individualistic secession from the world is a most dangerous form of treason, in comparison to which the rapes, knifings, stolen bread, and liquor of the underclass are all too easy to forgive. For the latter are simply operating the system in their own disadvantaged way, with the same objectives, finally, as the capitalists and lords, whereas the thinkers seek to float away entirely. It is for this reason that in the camps, the political prisons were considered “external contradictions,” the criminals, “internal contradictions.”  The twentieth century was witness to no shortage of political violence and mass death perpetrated by the state. The two most well-known genocides of the century—those that occurred under the rule of Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union—did not occur because the state broke down and lawlessness prevailed. Quite the contrary: both regimes had complete control over their citizenry, and the apparatus of government was used to make the butchery as efficient and as inescapable as possible. Both regimes were characterized by extreme violence and terror, key elements of the totalitarian system as defined by Hannah Arendt, so it seems only logical that totalitarianism increases the potential for genocide.

The twentieth century was witness to no shortage of political violence and mass death perpetrated by the state. The two most well-known genocides of the century—those that occurred under the rule of Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union—did not occur because the state broke down and lawlessness prevailed. Quite the contrary: both regimes had complete control over their citizenry, and the apparatus of government was used to make the butchery as efficient and as inescapable as possible. Both regimes were characterized by extreme violence and terror, key elements of the totalitarian system as defined by Hannah Arendt, so it seems only logical that totalitarianism increases the potential for genocide.  In Italy, the transition from communism to post-communism, from the PCI to today’s Democratic Party, has been determined and strongly influenced not only by the collapse of ideologies and by the changes in the international political scene after 1989, but also by the profound changes that have invested the customs, lifestyles, and collective mentality from the end of the 1960s and, ever more rapidly, from the 1970s. Mass individualism and consumer society are the factors that more than others have undermined the myth of the anthropological “diversity” and the claim to moral superiority cultivated for decades by the Italian communists. Moreover, they help explain the passage of many of them from the utopia revolutionary and the dream of a “new world” to the liberal-bourgeois radicalism that seems to characterize today’s Italian left. Is there anything left of the communist tradition in today’s Italian political and cultural scenario? There is probably one attitude shared by many Communist militants but that belongs to the entire Italian political tradition, i.e., the deeply rooted aversion to public institutions and a poor sense of the state as embodying the rule of law. The greatest and most negative legacy of the long hegemony, on the left, of a communist party narrowly loyal to the Soviet Union was and still is the lack of legitimacy of the state and its institutions. The Soviet experiment having failed, there remains a populist cultural capital that has passed on to the Lega Nord in the 1990s and that has recently migrated to the Five Stars Movement of Beppe Grillo.

In Italy, the transition from communism to post-communism, from the PCI to today’s Democratic Party, has been determined and strongly influenced not only by the collapse of ideologies and by the changes in the international political scene after 1989, but also by the profound changes that have invested the customs, lifestyles, and collective mentality from the end of the 1960s and, ever more rapidly, from the 1970s. Mass individualism and consumer society are the factors that more than others have undermined the myth of the anthropological “diversity” and the claim to moral superiority cultivated for decades by the Italian communists. Moreover, they help explain the passage of many of them from the utopia revolutionary and the dream of a “new world” to the liberal-bourgeois radicalism that seems to characterize today’s Italian left. Is there anything left of the communist tradition in today’s Italian political and cultural scenario? There is probably one attitude shared by many Communist militants but that belongs to the entire Italian political tradition, i.e., the deeply rooted aversion to public institutions and a poor sense of the state as embodying the rule of law. The greatest and most negative legacy of the long hegemony, on the left, of a communist party narrowly loyal to the Soviet Union was and still is the lack of legitimacy of the state and its institutions. The Soviet experiment having failed, there remains a populist cultural capital that has passed on to the Lega Nord in the 1990s and that has recently migrated to the Five Stars Movement of Beppe Grillo.  It would be simplistic to argue that behind the Marxist critiques of capitalist society there was only an objective intention simply to improve its effectiveness and avoid the political complications found in capitalist society. Despite its strict scientific tone, Marxism still carries a heavily moral intention. This is what Georg Lukács comes to argue in this essay on culture. In his analysis of capitalist cultural structure and its many differences from capitalist reality, Lukács points to what he regards as the ultimate goal behind communism: a new cultural order.

It would be simplistic to argue that behind the Marxist critiques of capitalist society there was only an objective intention simply to improve its effectiveness and avoid the political complications found in capitalist society. Despite its strict scientific tone, Marxism still carries a heavily moral intention. This is what Georg Lukács comes to argue in this essay on culture. In his analysis of capitalist cultural structure and its many differences from capitalist reality, Lukács points to what he regards as the ultimate goal behind communism: a new cultural order.  This work results from the development of a Master’s thesis for the Master in Communication Sciences, at the Faculty of Arts of the University of Porto. My thesis was under the theme “The Communication of Communist Ideology after the Fall of the Berlin Wall: Limitations, Disruptions and Opportunities. The Portuguese Case: The Image of the Portuguese Communist Party in the 21st century.” Our main question is whether communism is recognized as being valid today. The thesis is based on a theoretical and methodological approach on the identity, historical background, and validity of certain vectors related to communist ideology in today’s society. The object of the work is the communist ideology, mainly the European communism and the Portuguese Communist Party. A second part of this research work is complemented with a study of the party’s image made after conducting a survey of 600 students from the University of Porto.

This work results from the development of a Master’s thesis for the Master in Communication Sciences, at the Faculty of Arts of the University of Porto. My thesis was under the theme “The Communication of Communist Ideology after the Fall of the Berlin Wall: Limitations, Disruptions and Opportunities. The Portuguese Case: The Image of the Portuguese Communist Party in the 21st century.” Our main question is whether communism is recognized as being valid today. The thesis is based on a theoretical and methodological approach on the identity, historical background, and validity of certain vectors related to communist ideology in today’s society. The object of the work is the communist ideology, mainly the European communism and the Portuguese Communist Party. A second part of this research work is complemented with a study of the party’s image made after conducting a survey of 600 students from the University of Porto.