In today’s episode of the Telos Press Podcast, David Pan talks with Xudong Zhang about his article “China and the West: Methodologies for Comparison,” from Telos 199 (Summer 2022). An excerpt of the article appears here. In their conversation they discuss how the specific comparison between China and the West leads to new methodologies of comparison; how a thematic mode of comparison works to bring China and the West in relation to each other; how the need for both a closed horizon, indicating a kind of self-isolation, and a common humanity relate to one another; how comparison can be framed within a context of both movement and action; and how comparison links the particular to the universal. If your university has an online subscription to Telos, you can read the full article at the Telos Online website. For non-subscribers, learn how your university can begin a subscription to Telos at our library recommendation page. Print copies of Telos 199 are available for purchase in our online store.

|

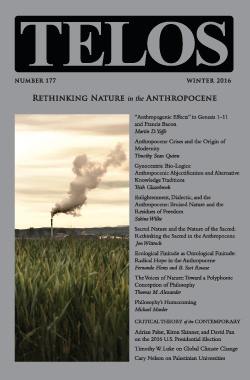

Telos 177 (Winter 2016) is now available for purchase in our store. Consider the Aristotelian maxim that humankind “is by nature a political animal,” whose capacity for speech, unique “among the animals[,] . . . serves to reveal the advantageous and the harmful, and hence also the just and the unjust.” If one accepts this dictum (and, crucial to this article’s line of thinking, by no means must one necessarily adhere to Aristotle’s rationalist model of “man,” nor any other universalist account of humanness), then the ceaseless question remains: what specific sort(s) of speaking, morally reasoning animal might the human be read as constituting, from within the interpretive mindset of a particular historical and civilizational milieu? Of course, this question presupposes, in a manner that may well be at odds with the anthropological premises of a universalist modern political doctrine like human rights, that, rather than exhibiting a fixed, unitary essence, the human acts as a signifier; as such, this human signifier might potentially refer to myriad worldviews, and sources and assemblages of contextualizing meaning, across which the understanding of humanness can be differently constructed and construed. Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar paints the portrait of a brave new time in the future when we will finally cut the shackles attaching us to our dying home planet and embrace our nomadic nature. Having turned the earth into a gigantic dust bowl, where the soil is increasingly barren and the air unbreathable, we will move on to greener pastures, in the shape of as yet unpolluted planets in faraway galaxies. After all, why shouldn’t planets be more like paper tissues—one soiled and tossed, another one already on the way? |

||||

|

Telos Press Publishing · PO Box 811 · Candor, NY 13743 · Phone: 212-228-6479 Privacy Policy · Data Protection Copyright © 2024 Telos Press Publishing · All Rights Reserved |

||||