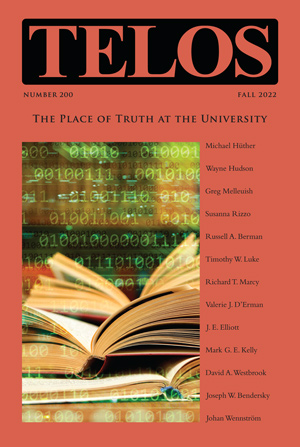

In today’s episode of the Telos Press Podcast, David Pan talks with Michael Hüther about his article “Tired of Science?! Notes on the Relationship between University and Society,” from Telos 200 (Fall 2022). An excerpt of the article appears here. In their conversation they discuss what has become problematic in the relationship between science and truth and the relationship between science and values; how we should understand the role of myth in human society and why it continues to be important; how moralization responds to the dissatisfaction with science and the continuing relevance of myth; the dangers of moralization for the university; the driving forces behind the economization of the university as well as the consequences of this economization; how the German constitution establishes the social and political roles of the university; and how the university fulfills these roles today. If your university has an online subscription to Telos, you can read the full article at the Telos Online website. For non-subscribers, learn how your university can begin a subscription to Telos at our library recommendation page. Print copies of Telos 200 are available for purchase in our online store.

Tired of Science?! Notes on the Relationship between University and Society

Michael Hüther

1. Dilemmas of Science: Tensions between University and Society

The German philosopher Hans Blumenberg formulated this over thirty years ago: “The great enigma of the closing second millennium is and will perhaps remain the growing aversion to science.”[1] Regardless of the time-related motivation and conditionality of his statement, Blumenberg draws our attention to dilemmas that are fundamentally formative for science due to the way they are linked. These are dilemmas that have not lost their significance since then but rather have increased in importance over the last decade.

The German philosopher Hans Blumenberg formulated this over thirty years ago: “The great enigma of the closing second millennium is and will perhaps remain the growing aversion to science.”[1] Regardless of the time-related motivation and conditionality of his statement, Blumenberg draws our attention to dilemmas that are fundamentally formative for science due to the way they are linked. These are dilemmas that have not lost their significance since then but rather have increased in importance over the last decade.

Contributing to this are social upheavals, political challenges, and global economic crises, on the one hand, and new normative function assignments for the university in the sense of “transformative science,” on the other hand. Socially articulated requirements put the university under stress and demand that research and teaching be aligned with these wishes, not only in terms of the objects of its research but also the shaping of its results as well as the attitude and the behavior of academics. All of this places a renewed and urgent focus on the interrelationship between the university and society, that is, on the question of what the university can give to society and what society demands, or can demand, of the university.[2] This is the core of what follows. Let us start with the dilemmas.

First, there is the dilemma of the absolute truth as a claim of science when it is only imperfectly satisfiable. “Truth as a goal of the highest rank, as an absolute good, one that in our tradition is, in the final instance, identical with God—as an argument, this notion is dead,” said Blumenberg. “Lonely speakers in remote academic ceremonies timidly still say now and again that science has sworn itself to truth and has to accept no limitations in keeping this vow.”[3] A matter of course—and yet, instead of hearing it in secluded ceremonial acts, we are currently reading it in the memoirs of a well-known German economist. For him, it was not just about “an exciting fight for scientifically founded truth” but rather, when he “found the truth, . . . to retain the authority to interpret.”[4] On the other hand, Blumenberg, with whom I agree, would take the same view as the German Federal Constitutional Court, which, to quote Wilhelm von Humboldt, understands truth as “something that has not yet been completely found and can never be fully found.”[5]

Therefore, German constitutional law does not protect a certain conception of science or a certain philosophy of science. Rather, its guarantee of freedom extends to any scientific activity that, in terms of content and form, is to be regarded as a serious, intentional attempt to strive for the truth. This reflects the fundamental incompleteness of any scientific knowledge. The provisional nature of all knowledge demands humility toward the striving for truth, which satisfies its claim by generating doubt.

Second, there is the specific dilemma that arises from the indeterminacy of scientific endeavors for the observer. The urgency of further research, in view of the status it has reached, results less and less from an apparent need for problem-solving in daily life. The meaning of scientific endeavor itself requires reflection. This is, for example, most evident today in Artificial Intelligence, where there is concern that we will ultimately submit to the computer and its algorithm. The philosopher Markus Gabriel not only convincingly identified this concern as an error but also named the increasing need for research and education in the humanities as an answer.[6] Thinking means processing raw data into information by distinguishing between the essential and the insignificant in order to reduce complexity and recognize patterns in reality.[7] This open thinking will always remain an individual and therefore normative achievement. The human ability to “think without a bannister,” in the wonderful formulation of Hannah Arendt, saves us from unnecessary worry when we are aware of the self-responsibility that lies within.

And, third, there is the dilemma that, although different in the various disciplines, is always unavoidable, namely, the normativity of science. This is evident in those disciplines that, like economics, deal with socially meaningful human behavior, as was most recently made public through demands for a “pluralistic economics.” In a dispute in the German weekly business newspaper Wirtschaftswoche, a professor of economics responded to criticism of this pluralistic perspective by pointing out that “the models . . . thanks to their mathematical underpinning are free of ideology.”[8] Well, mathematics certainly opens up a way for economics to penetrate problems precisely and consistently according to the rules of logic. The internal dispute between economists should not be discussed here, but this exemplifies the fact that a naive use of mathematics, as in neoclassical financial market economics, can be misleading. The global financial and economic crisis of 2008–9 was driven by mathematical risk models without institutions, which, due to a lack of market prices for each derivative, offered the model-based information that led to the extensive misallocation of financial capital. However, the application of mathematics is neither unconditional nor comprehensively possible, and it does not spare us value judgments, such as those that are indispensable for the development of theories about the image of man (the human condition).

These dilemmas—the dilemma of the inaccessible absolute truth, the dilemma of scientific indeterminacy, and the dilemma of inevitable normativity—give rise to a weariness with science. The associated excessive demands lead to a loss of confidence and rejection reactions. The COVID-19 pandemic has also changed the role of science in public discourse and in relation to politics. Disciplines were in demand from which one expects exact statements without an expiration date. After all, it was a matter of life and death. But even here you must pay hardship, and our knowledge bridges our ignorance only temporarily; even here there is scope for assessment and gaps in understanding that are not always easily resolvable; even here the preferences and attitudes of the scientists are at play. The obvious demand for an increased interdisciplinary exchange is good and correct, but not without preconditions. For this requires assessing the limits of one’s own subject and seeing the normative conditions at work when turning scientific knowledge into political recommendation.

The dilemmas mentioned have thus intensified again during the pandemic crisis. Loss of confidence and rejection reactions turn out to be particularly serious in our time because they coincide with two significant trends of political and social change: moralization and economization.

• On the one hand, moralization counteracts the weariness with science by asking the permissible questions and shaping the acceptable results to the value judgments of third parties, who claim sovereignty over the discourse.

• On the other hand, economization counteracts the boredom with science. Through efficient, market-driven competition for financial resources, markets take over the program definition of science. Users’ preferences and willingness to pay are decisive.

Continue reading this article at the Telos Online website. If your library does not yet subscribe to Telos, visit our library recommendation page to let them know how.

* An earlier version of this essay was published in German as “Überdruss an der Wissenschaft?! Anmerkungen zur Wechselbeziehung zwischen Universität und Gesellschaft,” in Gießener Universitätsblätter 52 (2019): 69–77.

1. Hans Blumenberg, Care Crosses the River, trans. Paul Fleming (Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press, 2010), p. 49.

2. Jürgen Mittelstraß, “Die Universität und ihre Gesellschaft,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, July 23, 2018; Peter Strohschneider, “Zur Politik der transformativen Wissenschaft,” in Die Verfassung des Politischen, ed. André Brodocz et al. (Wiesbaden: Springer, 2014), pp. 175–92.

3. Blumenberg, Care Crosses the River, p. 50.

4. Hans-Werner Sinn, Auf der Suche nach der Wahrheit (Munich: Herder, 2018), p. 583.

5. German Constitutional Court Decisions, BVerfGE 35, 79, 113.

6. Markus Gabriel, Der Sinn des Denkens (Berlin: Ullstein, 2018), p. 195.

7. Ibid., p. 35.

8. Bert Losse and Katharina Matheis, “‘Viele Professoren haben kein echtes Interesse an der Lehre,'” Wirtschaftswoche, no. 15, April 4, 2015, p. 35.