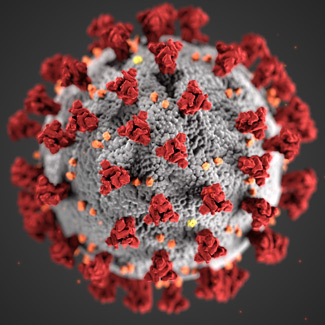

Social and economic disruptions in the wake of this spring’s virus will be unevenly distributed in intensity and time. Socially distanced rural suffering will long outlast the news cycle and panic.

COVID-19 is a real crisis. It is unique for being concentrated for once in places where global travelers, professionals, and creatives live. When risk for those populations is controlled to a level they can accept, expect panic and restrictions to ease. Our world happily tolerates death tolls far in excess of the worst projected for COVID-19 when only rural people or people with a high school education or less are at high risk.

COVID-19 is a real crisis. It is unique for being concentrated for once in places where global travelers, professionals, and creatives live. When risk for those populations is controlled to a level they can accept, expect panic and restrictions to ease. Our world happily tolerates death tolls far in excess of the worst projected for COVID-19 when only rural people or people with a high school education or less are at high risk.

Kentucky, where I live, expects our COVID-19 crisis to peak on Saturday, May 16, with 1,600 hospitalized and 240 in ICU beds on that day. By then, New York is expected to no longer need any COVID-19 beds. Their peak will have been a month and a half previous. Kentucky (more accurately, Lexington and Louisville) will probably be fine when we peak. Tennessee (e.g., Nashville and Memphis) probably won’t. Expect the news to have moved on by then.

Kentucky expects less than 900 COVID-19 deaths this year. We also still expect our normal of upward of ten thousand heart disease and cancer deaths, 3,500 chronic lower respiratory disease deaths, and 3,300 accidents (1,600 of the accidents will be drug overdoses and 730 firearm deaths; gun deaths are mostly suicides). According to the CDC, the next seven causes of death in Kentucky—which all remain more likely than death by COVID-19—are stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, kidney disease, septicemia, and flu/pneumonia. Early death from these causes is most likely among rural people and people with less than a high school education, and is unremarkable.

It is too early to say how impacts of this spring—such as missed medical appointments, furloughed health care workers, small businesses failing or being bought out by monopolies and private equity firms, higher health insurance premiums, local government budget shortfalls, distressed and broken families, and a possible economic depression—will affect normal causes of death in Kentucky. Since at least Durkheim’s 1897 study on the topic, it has been known that social isolation increases the suicide rate. Without significant political pressure, increases in hazard that are largely contained away from professionals and creatives will be tolerated.

Globally, the unremarkability of early death in less cosmopolitan classes and places is more extreme. The nearly landlocked Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, is arguably in Africa’s “flyover country,” despite its megacity, Kinshasa. It has no or nearly no cases of COVID-19. However, the country is in a grade 3 public health emergency, the same WHO rating as Italy. Why? First on the list is a virus I can’t even spell: Chikungunya virus disease. Also the fifth year of a cholera outbreak, the third year of an Ebola virus outbreak, the second year of a measles virus outbreak, the third year of a monkeypox outbreak, the second year of a “plague” nobody with research dollars cares enough about to do the science to specify what exactly it is, the third year of a vaccine-associated acute paralytic polio, and—the kicker—the aftermath of war. The economic interests that destabilized the public health capacities of Europe and the United States in the last 25 years (most acutely since the global financial crisis) cut their teeth with structural adjustment and imposed austerity programs in Latin America in the 1970s, Africa in the 1980s, and the former Soviet Union in the 1990s. The people who did most of the dying during those apocalypses are remembered as, well, just the sort of people who die.

In a fiery essay in the Players Tribune, the Miami Heat’s power forward Udonis Haslem described the consequences of the selfishness of Miami spring breakers.

You see that video going around of these silly a** college kids down in South Florida on spring break? Talking about, ‘If I get corona, I get corona, bro,’ and all that nonsense? . . . When the average person in Middle America thinks about . . . social distancing . . . , maybe they picture a bunch of schools shutting down and then these kids going home to a bunch of nice houses and chilling for a couple months. Eating snacks, playing video games. Mom’s working from home, doing conference calls. . . .

For a lot of kids, the truth is that school is the only structure they got. It’s the only food they can count on. It’s the only safety that’s guaranteed. You take that all away? You better be prepared to protect them. . . . If you got a roof over your head and some food in your fridge and you don’t have to go to work to feed your family, just do the easiest thing in the world, man. F*** your spring break. Just keep your a** at home.

What he wrote about spring breakers could easily be said about cosmopolitan entrepreneurs (social or otherwise), nonprofit managers, partiers, artists, and urban professionals in the hardest-hit cities—New York, New Orleans, and Detroit. It’s maybe no coincidence that those three cities were the most attractive to highly mobile creative-class people I’ve known in the last decade. Through conferences, weddings, vacations, and other irresponsible travel, mobile professionals and creatives and their wealthy patrons are vectors for a plague that will ultimately hurt them far less than it will hurt people they don’t think matter.

I live in a poor county within an afternoon drive of some of the poorest in America. The last two hospitals I worked in routinely take patients from 300 miles away and employ staff who commute a hundred miles each way (e.g., Lost Creek to Lexington). In an insightful book review, in the New York Review of Books, Helen Epstein described how my rural neighbors may react to an economic shutdown over the coming months with suicide, conspiracy theory, and physical pain. While these things may endure, the COVID-19 panic will last only as long as our betters are at risk. As I socially distance, I watch my brother, my neighborhood, the truck stop, my workplace, and the places and people I love. What do forgotten people who live in our neighborhoods or our counties need, materially and culturally? What will we need once our betters feel safe and have liquidity, but the place where we used to work has closed forever? It is time to somehow carry those we love with us, not through a snowstorm but through a long winter.

We live together on the Titanic. If first-class cabins are taking on water, steerage was long ago flooded to its roof. Governors have worked to protect us, but the federal executive and legislature of my country are now enacting policy like the CARES Act that pumps water out of first class into the few remaining airspaces of second- and third-class cabins. Debt forgiveness, uncapped federal programs with clear qualifying events, and the universal, legally enforceable right to health care and paid work would be a whole new boat.

I am not suggesting more grants for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to do plague research in Africa. Nor do I argue that Kentuckians should defy social distancing orders and go to church. I am merely noting that the source of our present panic is an apocalyptic moment spread by and touching the lives of those who at best administrate the apocalypses of others in what they consider normal times.

Correction

The model predicting peak resource use and mortality was radically revised on April 7. Kentucky is now expected to peak on Friday, April 24, three weeks sooner than previously predicted. Peaks in New York and Louisiana were expected and observed on April 8.

Urban resource use and deaths continue to be expected to decline as resource use and deaths increase in rural areas. Some deaths remain more newsworthy than others—evidenced by the underreported outbreak in southwest Georgia’s rural black belt, where confirmed cases and mortality per resident have rapidly outpaced New York City’s in four counties. Social distancing retains its dual nature as a necessity and a threat.

As events continue to unfold and history replaces predictions, this essay will not be corrected again.

Anna G. Keller is a public health analyst and mental health technician. A version of this essay first appeared on the author’s website.