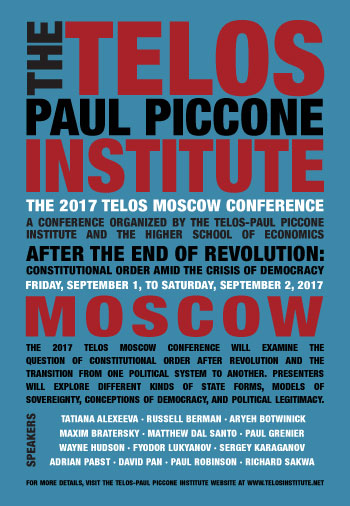

The following paper was presented at the conference “After the End of Revolution: Constitutional Order amid the Crisis of Democracy,” co-organized by the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute and the National Research University Higher School of Economics, September 1–2, 2017, Moscow. For additional details about the conference as well as other upcoming events, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

Today is the time when we get to discuss our future together. This is a rare occasion that may or may not occur every hundred years. For once, we now have Russians, Americans, and Europeans sitting in one boat and considering together how to pass the rapids without capsizing. Steering out of the impasse where we have been driven by the global crisis requires clear thinking and direct, candid dialogue, i.e., the return to the “direct statement” culture. And this is exactly the way in which I will take the liberty to speak. I term the manner of speaking plainly in scientific discussions as “intellectual diplomacy.” And there are times when it is capable of achieving greater results than the combined efforts of the foreign ministries of a number of countries of the world.

The genre of scientific futurology has always attracted public interest. In the same way, applicability criteria for any scientific theory should always include predictive abilities. Yet there is a current feeling today that discussing the future has achieved levels of passion unseen before. And that is the feeling that both men of science and ordinary people share.

The genre of scientific futurology has always attracted public interest. In the same way, applicability criteria for any scientific theory should always include predictive abilities. Yet there is a current feeling today that discussing the future has achieved levels of passion unseen before. And that is the feeling that both men of science and ordinary people share.

For us Russians, the situation is a familiar one: we experienced one just like it in the Soviet Union before perestroika, in the early 1980s. Only now, it is definitely bigger. Indeed, it is quite possible that today we are facing a new, this time global, restructuring.

I

It was only until recently that achieving neoliberal consensus was considered the single requirement to ensure the sustainable development of society on a global scale. This is what Francis Fukuyama meant by the concept of the “end of history.” As recently as this year, however, Fukuyama has publicly renounced his idea. The end of history has failed to occur and is nowhere in sight. Fukuyama was wrong. The “clash of civilizations” theory of Samuel Huntington also loses its explanatory power, as it places the modern West in the role of the uncontroversial “civilization No. 1” that finds itself in conflict with outsiders, with the “existential Other.”

The recent years saw a serious split within the ruling “golden billion” elite concerning a number of issues. Are new points of conflict on the global margins worth creating? Is it safe to continue with the issuing of the dollar? Whether to go for Trans-Atlantic or Trans-Pacific partnership? The global financial system and the political stability of the world are becoming increasingly difficult to control. Many previously tame processes run wild. Take such recent surprises as Brexit, the victory of a non-system candidate in the United States, the Russians in the Crimea reuniting with their great Motherland, the failure of liberal revolution in Turkey, and the success of the Assad coalition in Syria. None of these would have been possible under the old political and economic regime, which is now facing irreversible changes. As the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev used to say in such cases, “The process of change is on.”

The old paradigm no longer functions. Despite its civilizing messianic ideology and humanistic rhetoric, we now watch the system taking an archaic turn, as it relies increasingly on the ultra-right ideology. As the Russian philosopher Alexander Panarin commented on the subject, New Democrats display a racist way of thinking, as they renounce both Christian and enlightenment universalism values. They have replaced the noble openness of enlightenment with the esoteric idea of “democratic” racism, associated with the belief that there is a special type of mentality suitable for democracy that the European “white man” is endowed with.

As it is now becoming evident in Russia, the system of liberal values is getting increasingly at odds not only with ethical standards but also with objective reality. It is impossible to simultaneously discuss the free market and human rights and maintain sanctions. It is equally meaningless to talk about democratic procedures, when election becomes a struggle of compromising materials rather than a struggle of ideas. Where the media is bought wholesale by one of the parties, there is no longer any freedom of press. The idea of a national choice is meaningless when the right to independence is granted to one kind of nation but withheld from others.

Meanwhile, protecting the interests of minorities has evolved into active discrimination against the majority, and Christianophobia has become commonplace. The sprouting of missionaries and apocalyptic chimeras, along with a number of Western governments searching obsessively for the enemy in the form of an “axis of evil” or “rogue states,” insistently call to mind Berdyaev’s idea of the “New Middle Ages.”

Shortly before the presidential election, Donald Trump offered the Serbs his apologies for the bombing of Belgrade by NATO aircraft, only to be rewarded with the label “fascist,” as opposed to those who actually gave the orders to bomb Belgrade, Iraq, and Libya. As if in keeping with Orwell’s dystopia, the U.S. government forbids their citizens to visit the “wrong” country—North Korea. It was not so long ago that the members of the band Scooter were actually threatened with 8-year prison sentences after playing a concert in Balaclava. This is strangely evocative of the 1990s story of the American chess player Bobby Fischer, who had been forced to leave the country after playing a match with Boris Spassky in Belgrade.

As the leader of the Russian Church Patriarch Kirill recently pointed out, almost nothing is now left of the “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” slogan of the French revolution. There has been no equality or fraternity to speak of for a long time, while liberty has become a tool of manipulation.

There are ongoing attempts to justify social inequality with racist doctrines, only barely veiled with euphemisms and empty political clichés. There is no way, for example, that replacing the concept of “cultural inferiority” with “non-conformance to democratic standards” is going to work for a clear-headed audience: euphemisms are a product of the language and not of sociopolitical reality. It is, in fact, its own inner barbarian, veiled with a thin layer of pseudo-democratic rhetoric about protecting the freedoms and rights, which the West thereby reveals. Small wonder that the United States and Canada chose not to support the United Nations initiative to outlaw Nazism glorification in 2014.

II

Modern political jargon analysis reveals a certain number of repeatedly used concepts that have long lost their meaning, “open society,” “totalitarianism,” and “democracy standards” among them. The stagnant character of modern sociopolitical language and the overabundance of idioms betray the vicious circle that modern politics keeps following, leaving world problems unsolved. This is a crisis of confidence, a crisis of legitimacy, and ultimately a crisis of ideas.

On a theoretical level, the situation has been long predicted by Immanuel Wallerstein—ever since he gave one of his books the title After Liberalism. As we can see it now, however, he was not entirely accurate. What we are witnessing today is modern neoliberalism, which is a direct result of the absorption of neighboring left and conservative ideologies, and also the reason of the forced unanimity that we see in the modern society.

Essentially, neoliberal ideological discourse is a construct of the ultra-liberal, quasi-socialist, and quasi-conservative ideas. The use of “quasi” in the last two cases is imperative. In fact, it is the conservation of the existing world order, and not traditional values, that conditional conservatism specializes in. Instead of solving social problems, all that the conventionally “left” trend actually does is practice selective human rights protection and cater to the interests of different minorities. The neoliberal world is passing through a phase of obscuration, and showing signs of rapid cultural regression.

The process of self-destruction and the archaic turn that the modern society is taking poses equal dangers for the perpetrators and for their victims. What the modern society needs is a radical shift of paradigm. That requires a development model that may incorporate different visions of the future. As recently as the end of the twentieth century, there existed a number of versions of this model. Today—largely because of our own inaction—our future options are extremely narrowed.

The global elite, or as the Americans like to style them, the “deep state,” is confronted with a choice: to keep on trying to control the world by means of fueling conflicts or to accept the fact that globalization has reached its limits and start dismantling the political, economic, and ideological framework of the modern Western project. The first option will undoubtedly bring on new “humanitarian” bombings, fresh economic sanctions, and support right-wing circles in the satellite countries (Ukraine, the Baltic States, Poland, a part of Syria, etc.). It will inevitably cost great sacrifices and a lot of blood, while offering only a brief historical reprieve before radical solutions to problems will have to be found. There’s no scenario that can do more than influence the timing of the coming changes. At the present stage, they are impossible to cancel. It’s the question of time, not of principle. It therefore makes sense to start considering the second scenario that will involve a radical change of development paradigm.

The first thing to do is to recognize the futility, fallacy, and immorality of colonial capitalism and neoliberal globalism as models of development. No future improvement is possible without prior recognition of the common historical and ideological basis of first colonial, then Nazi, and finally globalist projects. Colonialism, Nazism, and Globalism make up the complex of ideas that we must totally reject. Renouncement of all forms of the civilizational superiority doctrine is crucial to making future changes stable and predictable.

It is equally imperative to understand that Nazism and Bolshevism are not just two separate “totalitarian regimes,” but constitute integral parts of a centuries-old totalitarian project based on vulgar interpretations of naturalism and positivism. Although the history of the last three centuries was largely distorted by fanatical followers of this doctrine, it fortunately also encompasses examples of moral stoicism, spiritual resistance, and creativity of people who were strong enough to keep their lives independent from the spiritual enslavement of this dead ideology.

The second thing to recognize is the pathological nature of consciousness based on society rejecting its own Christian tradition. With the exception of the West, no other civilization in the world has ever founded its development upon rejection and destruction of its own initial tradition. This is the exclusive property of “first world” consciousness. Therefore, overcoming the painful Christianophobia and historical vandalism is both compulsory before restoring fundamental social foundations can be considered.

Restoring the tradition also involves maintaining the classical rationality values and the scientific critical thinking that will have to be weeded for ideological speculations of naturalism and positivism. There cannot be a full recovery of Christian universalism without a return to genuine rationality.

When both conditions are met, the Western society will finally embark on a path of healing and spiritual repatriation.

III

Although the idea of a conservative alternative to authoritarian neoliberalism is common talk today, it raises many questions. Historically, conservatism purported to the reaction of the “old regime” representatives toward the bourgeois revolution and belonged to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Those are long gone. Then what is there to preserve? Christian values? Aren’t they being forcibly expelled from modern society? The only situational conservatism we see today is nothing but servile in character, obedient to the obsolete system, where the rights and economic freedoms only exist for the selected few at the expense of others. Modern conservatism is devoid of agenda and totally loses its meaning when faced with artificial social differences and endless “innovation.” Today, the single purpose for declaring a conservative position may be to rearrange your set of concepts in a more attractive way, while still adhering to the principle of things. In other words, to stall the changes. Suppressing them without social violence, however, has become impossible.

Provided that socialism finds the strength to escape from the suffocating embrace of neoliberalism, it also has a future. Do not, however, confuse the socialism of today with the Soviet and especially with the Communist version. Contrary to conservative and liberal criticism, this kind of socialism does not renounce private property. The only kind of property it is opposed to is big capital and transnational financial oligarchy, both of which impede real democracy. It supports the idea of a sovereign state that offers broad social and economic guarantees. Since this can only be made possible with the support of the state and relies upon the traditional model of social communication, this kind of socialism advocates a strong national government and active Church involvement, as well as promotes strong family values and moral criteria. Not only is this kind of socialism inseparable from traditionalism, it takes its origins there directly.

We are going through a unique historical period characterized by the inevitable transformation of the well-known political spectrum. Instead of the familiar “conservatism-liberalism-socialism” triad, we will soon find ourselves within another triangle of “nationalism-socialism-traditionalism.”

It is unlikely that nationalism will ever be an independent ideological trend. It is much more plausible that it will become an integral part of other ideologies. There are two different varieties of nationalism today. One of them is neo-Nazism, exploited by the transnational financial oligarchy for reshaping territories, markets, demographic, and cultural-linguistic spaces. The other is the kind of nationalism that has long cultural, linguistic, and historical roots, and to which the idea of racial inequality is totally foreign. It is the second type that is continuously attacked by the positivist and constructivist ideology that treats nations as “imagined communities.”

And finally, tradition and traditionalism. Being the forming factor for a new ideological paradigm, they also create the vanishing point for its socialist and traditionalist proper parts, as well as for elements of democratic cultural nationalism. The social-traditionalist model of society development includes statist government and fair distribution of public goods. As the past and the future are finally reconciled in people’s minds, a synthesis of the “heritage” and “project” modalities of history serves to eliminate historical gaps.

Within the framework of the traditionalist social model, traditionalism has two meanings, one of which pertains to a local (or national) culture and the other—to universal. In its broadest, universal sense, traditionalism means respect for all traditions as the basis of democracy and socio-genesis, unless they profess ideas of superiority. All cultures and civilization are unique in equal measure, as the law of their incomparability and incommensurability, or the principle of “cultural and value pluralism” comes into force.

Once the social-traditionalist model of society finds realization, the concept of the “tradition–modernity” dichotomy will become a thing of the past. Today, it is most often one of the existing traditions that claims global status under the guise of modernity, which is a relic of the colonialist mindset. In such cases, cultural and historical features are presented as peculiar historical stages. The substitution within this approach is clear and obvious. Some representatives of the political elites will have to rethink the past and to recognize the fact that after having been imposed on people for several centuries, colonialist ideology gave rise to both Nazism as its radical form and communism as the authoritarian reaction to it.

Thus, social traditionalism takes over the function of creating ideological consensus, in which the ideas of socialism, cultural nationalism, religion, and tradition proper are able to coexist. Social traditionalism can serve as the foundation for restoring the real democratic rights to the majority. Since traditions are the only values binding together all the social strata, a real democratic system can only be based on tradition.

IV

Repressing mistakes and crimes out of the historical memory is totally unacceptable. A thinking man will hardly share outdated ideas of cultural, racial, and civilizational superiority. Those phantoms of false consciousness have done us enough harm. What is required now is a sober view of history and a deep restructuring of cultural and social policy, plus a complete rejection of the barbaric ideology of the twentieth century, which used to elevate some people over others, and place material values over moral. The period of voluntary historic savagery comes to its end. It is time to finally turn over this page of history and put an end to the licensing of civilized rights.

While the inertia of the colonialist project is still strong, the foundation of this doctrine has already been shaken. Our task is to carefully dismantle and deactivate the project before it collapses on top of us. We need to evacuate the dangerous ideological area before our historical time runs out.

A “New Grand” style is knocking for admission into the hearts of Europeans, Russians, Americans, Africans, Asians, and Australians. It lays waste to the industry of lies and fraud. People start seeking to regain the legal right to speak in direct statements, to use a more humane language for communication, and to create more humane relationships. The time for taking strategic decisions about moving along the new path is our immediate future. And this is one of the purposes that intellectual diplomacy is called upon to serve.

Aleksandr Shchipkov is Doctor of Political Sciences, advisor to the Chairman of the State Duma of the Russian Federation, Member of the Public Chamber of the Russian Federation, and First Deputy Chairman of the Synodal Department of Public Relations of Moscow Patriarchy of Russian Orthodox Church.