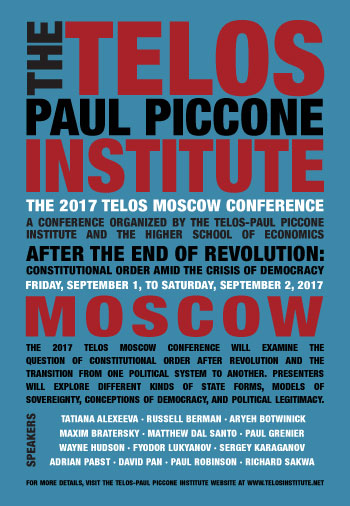

The following paper was presented at the conference “After the End of Revolution: Constitutional Order amid the Crisis of Democracy,” co-organized by the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute and the National Research University Higher School of Economics, September 1–2, 2017, Moscow. For additional details about the conference as well as other upcoming events, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

This presentation compares two societies, which, although both claim to be “Western” as well as vibrant liberal democracies, are in many aspects quite different. Those societies have been shaped by their history and political culture to evolve in quite different directions. Nevertheless, they can both be seen as “post-revolutionary” societies.

This presentation compares two societies, which, although both claim to be “Western” as well as vibrant liberal democracies, are in many aspects quite different. Those societies have been shaped by their history and political culture to evolve in quite different directions. Nevertheless, they can both be seen as “post-revolutionary” societies.

Poland has had a very checkered history, from being a Great Power, to disappearing from the map of Europe, which has contributed to a strongly “erotic” sense of belonging among the Poles.

Poland after 1989—the so-called Third Republic—has been in the difficult process of attempting a restoration of a more traditional Polish society, whose organic evolution and development had been so cruelly interrupted since 1939.

The former Communists in the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) were able to dominate the Parliament for most of the years up to 2005, as well as holding the presidency from 1995 to 2005. After the failure of the Olszewski government in 1992, and of the Law and Justice Party in 2005 to 2007, it appeared that the globalizing left had won in Poland, in the form of the post-2007 Civic Platform government, which was neo-liberal in economics, and left-liberal on most social, national, and historical questions. They also held the presidency from 2010 to 2015. Nevertheless, in 2015, the center-right Law and Justice Party won both the Presidency, and an absolute majority in the Parliament. The left immediately began street protests against the government, claiming that democracy was in danger.

The Sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) of Canadian Confederation is being celebrated in 2017 (July 1). Nevertheless, it is clear that Canada today is diametrically different from what it was in 1967 (the Centennial), let alone 1867. Canada was founded in 1867 as a union of two, long-preexistent, historic nations: English (British) Canada and French Canada (centered mostly in Quebec). The Aboriginal peoples were included insofar as they had been traditionally considered under the special protection of the Crown.

Liberal Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau (1968–1984, except for nine months in 1979–1980) inaugurated massive, transformational change that continues to this day (although he was also building on the transformations enacted by the administration of Liberal Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, 1963–1968): official bilingualism (promotion of French); official multiculturalism; mass, dissimilar immigration; high deficits; official feminism; and multifarious social liberalism. In 1982, Trudeau brought in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms into the Canadian constitutional structure, which essentially enshrined virtually his entire agenda as the highest law of the land. The enactment of the Charter was seen by both its supporters and opponents as a virtual coup d’état. The Charter was quickly backed up by a newly activist judiciary and a Canadian Supreme Court where it was difficult to find even one identifiable conservative.[1]

In 1984, Progressive Conservative Brian Mulroney won one of the largest majorities in Canadian history. However, he governed with unusual timidity, and was himself mostly a “small-l liberal” viscerally. Indeed, he kept down “small-c conservative” tendencies within the P.C. party. The term “small-c conservative” refers to so-called “ideological” conservatives. Mulroney once snidely said that you could fit all the ideological conservatives in Canada into a phone booth. Indeed, they were widely derided as “cashew-conservatives,” that is, nuts.

After the Harper Conservative government of 2006–2015 (for which the groundwork was laid by the earlier electoral insurgency of the Reform Party and the Canadian Alliance), the Liberals came roaring back with a strong majority in the October 2015 federal election, under the leadership of Justin Trudeau (Pierre’s son). The coming to power of another Trudeau presages another era of massive, transformational change in Canada. Indeed, immigration has already been raised to 300,000 persons a year, and there have been serious suggestions to raise it as high as 450,000 persons a year. Abortion rights and same-sex marriage have also been tightly entrenched. Also, doctor-assisted suicide is now legal, and complete marijuana legalization appears to be inevitable. Countervailing efforts by Preston Manning and Stephen Harper have failed to change the structures of the so-called “Trudeaupia,” which is now being cemented further into place by Justin Trudeau.

Ironically, it could be argued that there could be seen a greater pluralism of beliefs, and of authentic freedom of thought and speech, in post-Communist Poland, than in post-Trudeau Canada. Indeed, the Polish Right has recovered far better in the wake of the collapse of Communism, than Canada’s increasingly anemic conservatism has fared in the wake of the Trudeau revolution. There can certainly be seen a greater pluralism of ideas in the Polish academy and media than in the Canadian academy and media today. Canada appears to be driving to extirpate the last vestiges of tradition from its society, where to be a serious conservative active in social, political, and cultural life “will be made impossible.” In Poland, by contrast, there are a huge number of well-known conservative, right-wing, and nationalist personalities, who are not only surviving, but actually thriving. If some Western Europeans tendentiously accuse Poland of being “a country without a left,” then a far more apt accusation against Canada is that it is “a country without a right.” While there certainly were attempts to impose managerial-therapeutic structures on Poland, they have not gotten very far.

When Poles vote in their democratic elections, they still have a far broader variety of seriously contending parties, with different outlooks to choose from, than is the case in Canada. Poland can be seen as a “national democracy” where the historic nation and its cultural and religious identities still exercise a profound influence on politics—regardless of differences in economic approaches—whereas Canada is emphatically a late-modern “liberal democracy” where there is very little sense of the English Canadian and French Canadian historic nations and their respective religious denominations that once formed Canada. Indeed, Justin Trudeau has proclaimed that Canada is a “post-national state,” and he is, of course, extending and deepening official multiculturalism. With the continuation of very high immigration policies, it seems that within little more than a hundred years, Canada’s historic populations will have almost entirely disappeared.[2] That does not seem likely to occur in regard to the Polish population.

Without considering the broader social and cultural context of present-day Canada, it is not easy to see how very difficult the situation is for small-c conservatives and social conservatives.

It has been argued that there has emerged today, in most Western societies, something called (by its critics) “the managerial-therapeutic regime.” The term is derived from a combination of the ideas of James Burnham, author of The Managerial Revolution (1941), and Philip Rieff, author of The Triumph of the Therapeutic (1966).[3] Similar critical observations were echoed by George Parkin Grant (1918–1988), Canada’s leading traditionalist philosopher.

It could be argued that Canada today is among the fullest embodiments of such a regime, which is mainly socially liberal and economically conservative. As George Grant had aphoristically put it: “The directors of General Motors and the followers of Professor [Herbert] Marcuse sail down the same river in different boats.” There are discernible plutocratic aspects to modern-day Canada, and wide swaths of the population are unemployed or underemployed in what is, at least for some people, a “hyper-competitive” environment.

The managerial-therapeutic regime is based on relatively new structures of social, political, and cultural control. The structures of such a regime could in fact be seen as objectively anti-democratic, as giving rise to a so-called “democratic deficit.” Nevertheless, the structures of a regime of this kind are usually able to exercise power in a “soft” fashion. These consist mainly of: the mass media (in their main aspects of promotion of consumerism and the pop-culture, not to mention the shaping of social and political reality through the purveying of news); the mass education system (an apparatus of mostly unidirectional instruction from early-childhood education to post-graduate studies); and the juridical system (generally speaking, by way of the “judicialization” of important political questions and, more specifically, through restrictions on political and religious speech, and on freedom of religion, by human rights commissions/tribunals).[4]

The diffuse presence of these structures in society throws into question longstanding, classic understandings of government, politics, and democratic self-governance. The right to exercise freedom of speech, a supposed bedrock of democracy, is no longer valued much, even in theory—as opposed to the imperative of being “politically correct.” Democracy today is no longer understood as a vehicle for choosing between somewhat differing visions of politics and life, but rather as one, all-encompassing system of “democratic values” that must be upheld and imposed on everyone in society. The word “democratic” is usually used with the implied meaning of “socially liberal.”

The tendentious social and legal instruments of the regime are so deeply entrenched in Canada’s social/cultural fabric, moreover, that they are more than adequate when it comes to containing any popular challenges to the regime, whether these stem from the resistance mounted by residual traditionalist enclaves or from more thoroughgoing and deeply rooted channels of ecological or social democratic thought.

It could be argued that the regime is strengthened further by a “pseudo-dialectic of opposition” between an “official” Left and Right, which serves to exclude from the very outset many truly serious issues from public debate and consideration. Thus, elections may bring different parties and candidates into office, but the managerial-therapeutic regime endures.

The end-result of such a regime is a tendency toward so-called “soft totalitarianism,” of which the best known literary foreshadowing is probably the dystopia portrayed by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World (1932). In contradistinction to George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), an apparatus of violent coercion has proven unnecessary to maintain the regime. However, the points Orwell made about the importance of the use of language—”Newspeak is Ingsoc, and Ingsoc is Newspeak”—remain pertinent.

When a regime controls the mass media, the mass education system, and the juridical apparatus, it does not need to exercise massive coercion to keep itself in power. Opponents of the system are frequently enough derided as “haters” or “Luddites.” Unlike in the case of the former Eastern Bloc, there is no groundswell of tacit popular support for dissidents—indeed, quite pronounced feelings of seemingly popular outrage appear to be directed against them. Despite an ostensibly free society, they find very few public defenders.

So-called soft totalitarianism may in fact arise in the most ostensibly free and formally democratic systems.

Notes

1. This process of transformation was probably best critically described by Kenneth McDonald, His Pride, Our Fall: Recovering from the Trudeau Revolution (Toronto: Key Porter, 1995). This was the only book of several—such as The Monstrous Trick (1998)—by Kenneth McDonald that was published by a major publishing house. Another prominent critic of Trudeau is William D. Gairdner, the author of (among others) the bestselling The Trouble with Canada: A Citizen Speaks Out (Toronto: Stoddart, 1990); The War Against the Family: A Parent Speaks Out on the Political, Economic, and Social Policies That Threaten Us All (Toronto: Stoddart, 1992), and On Higher Ground: Reclaiming a Civil Society (Toronto: Stoddart, 1996). Peter Brimelow, The Patriot Game: National Dreams and Political Realities (Toronto: Key Porter, 1986) (reprinted in 1988 with the subtitle Canada and the Canadian Question Revisited) is one of the most pointed and nuanced critiques of “the new Canadian state.”

2. See, for example, Martin Collacott. “Opinion: Canada replacing its population a case of willful ignorance, greed, excess political correctness,” Vancouver Sun, June 4, 2017. Two major books and one policy report critical of Canada’s high immigration policies are: Daniel Stoffman, Who Gets In: What’s Wrong with Canada’s Immigration Program—and How to Fix It (Toronto: Macfarlane, Walter & Ross, 2002), Diane Francis, Immigration: The Economic Case (Toronto: Key Porter, 2002), and Martin Collacott, Canada’s Immigration Policy: The Need for Major Reform (Vancouver: Fraser Institute, February 2003). The most recent work focusing on these issues is Ricardo Duchesne, Canada in Decay: Mass Immigration, Diversity, and the Ethnocide of Euro-Canadians (Black House, 2017).

3. The critique of the managerial-therapeutic regime is explored further in the works of Christopher Lasch, such as The Culture of Narcissism (1979), The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics (1991), and The Revolt of the Elites: and the Betrayal of Democracy (1995), as well as by Paul Edward Gottfried, especially in his After Liberalism: Mass Democracy in the Managerial State (1999) and Multiculturalism and the Politics of Guilt: Toward a Secular Theocracy (2002). Christopher Lasch, it may be noted, identified himself as a social democrat to the very end of his life.

4. The operations of these human rights commissions/tribunals have been described in detail in Ezra Levant, Shakedown: How Our Government is Undermining Democracy in the Name of Human Rights (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2009).

There is very little comparison between post-1989 Poland and the new Canada. The article is mostly a critique of Canada’s so-called “managerial-therapeutic regime”. There is precious little about the PiS’s attempt to change Poland’s political system along more “nationalist” lines.