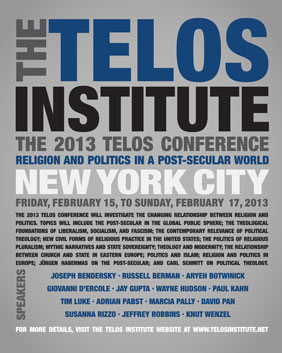

The following paper was presented at the Seventh Annual Telos Conference, held on February 15–17, 2013, in New York City. Bishop Giovanni D’Ercole is Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of L’Aquila, Italy.

In the paper I am presenting, I shall focus on how I think the Catholic Church can contribute to solving the crucial issues facing humankind today. I will do so by referring to two events that have marked the evolution of the Church in her dialogue with the modern world, namely, the publication of the encyclical Pacem In Terris, and the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council. We are currently celebrating the 50th anniversary of both events.

In the paper I am presenting, I shall focus on how I think the Catholic Church can contribute to solving the crucial issues facing humankind today. I will do so by referring to two events that have marked the evolution of the Church in her dialogue with the modern world, namely, the publication of the encyclical Pacem In Terris, and the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council. We are currently celebrating the 50th anniversary of both events.

A quick overview of the globalized world reveals the many contradictions and forms of injustice plaguing it. Underlying the crisis that has now taken on a global dimension is a three-fold question that characterizes what has come to be defined as the postmodern era. First of all, there is a fundamental question that is coming up again today, after the fall of totalitarian ideology. This is the anthropological question, a truly crucial question. The second question is related to the first. The social question has now become critical, and has to do with the very nature of man. Finally, the anthropological and the social question inevitably leads to the theological question, for man, by his very nature, is open to the transcendental and cannot be reduced to a creature that merely satisfies its material needs.

Humanity needs a God who is a merciful and provident Father in order for it to become aware of its vocation to be brothers to one another. The early encounter with the God of Jesus Christ awakened in many a thirst for love and solidarity towards one’s neighbor, and thus was born the Christian civilization that forged a large part of Western society. It humanized social and political structures, gave life to a more than millenary tradition of humanitarian and educational works as well as social promotion initiatives, and generated a host of saints. We can easily observe that in the course of the centuries, and especially at the end of the 19th century, the Church has constantly reflected on the social issue, by connecting it closely to the anthropological and theological question, as had been done previously by the Second Vatican Council. Please allow me to briefly reflect here on the connection between the social, anthropological, and theological questions, taking as a starting point the two anniversaries mentioned above, namely the 50th anniversary of Pacem in Terris and of the Second Vatican Council, and particularly its last document, the Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et Spes.

The Encyclical Pacem in Terris was the last encyclical published by Pope John XXIII on April 11, 1963. The complete title of the encyclical is emblematic: “Encyclical Letter Pacem in Terris of Pope John XXIII to the venerable brethren the Patriarchs, Primates, Archbishops, Bishops and all other Local Ordinaries who are at Peace and in Communion with the Apostolic See, and to the Clergy and Faithful of the entire Catholic World, and to all Men of Good Will: On Establishing Universal Peace in Truth, Justice, Charity and Liberty.” The Pope addressed all men of good will, believers and nonbelievers alike, for the Church must look to a world without boundaries and without “blocs,” and does not belong to the East or to the West. He invites all nations and political communities to a process of dialogue and negotiations. The Pope states that we must look for that which unites us and leave aside that which divides us. It is the first time that an encyclical is addressed to men of good will. The theme of peace was dear to John XXII. He was a man of peace, and together with the Council fathers he faced the last great atomic crisis of the contemporary world, the Cuban missile crisis, back in October 1962 when the Council was just beginning. It would be difficult to understand John XXIII’s courageous statement about peace and the Second Vatican Council without considering the global context at that time. The Pope decided to intervene by making an appeal to John F. Kennedy, President of the United States, and Nikita Kruschev, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and President of the USSR. The appeal was successful and resulted in the end of the blockade that the United States had imposed upon Soviet ships transporting missiles to Cuba, and in the Soviet Union’s withdrawal of those ships. Following such events, Pope John XXIII felt that given the changed historical context, the Church had to speak out clearly and with determination on the issue of peace. That led to the idea, the drafting and the preparation of the encyclical Pacem in Terris, which was promulgated a few months later. With Pacem in Terris, the Pope stated not only that there is no such thing as a just war, but that the problems of modern society must be tackled by going back to the root of the problems themselves. Pope Angelo G. Roncalli writes that the Church must be attentive to the life of men and must be able to read the signs of the times, which are the recognition of the evangelical elements in the life of the men and women of our time. He then concludes the encyclical with a number of references that concern relations between the Church and the world in the social, economic and political sphere.

Let us consider the second element. It is against this historical backdrop that we should consider the second element of my talk: the reflection of the Second Vatican Council on the relationship between the Church and the modern world with the Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et Spes. Gaudium et Spes was approved with 2,307 votes in favor and 75 against, and it was promulgated by Pope Paul VI on December 8, 1965, on the very last day of the Council. It may thus be considered as the last word addressed by the Council fathers to the humanity of our time. The very incipit Gaudium et Spes makes reference to joy and hope and urges the Church, conceived as the people of God journeying through history, to enter into a fruitful dialogue with the main spheres of the modern world. After all, the world is the work of God and thus the place in which He manifests his presence. The mission of the Church is to build bridges of friendship and dialogue with men and women of good will and to work with them to promote peace, justice, basic freedoms and science. The novelty of the Council text lies in the fact that it has established a reciprocity between what the Church gives to the world and what she receives from it, “Whoever contributes to the development of the community of mankind on the level of family, culture, economic and social life, and national and international politics, according to the plan of God, is also contributing in no small way to the community of the Church.” As to what the Church gives to the world, in succinct terms it may be stated that the Church gives to the world divine life, the religious meaning of existence. The gift of divine life and of the sense of the religious is structured and granted in a different way, according to whether it refers to individuals, society or human activity. To individuals, the Church manifests the mystery of God that is man’s ultimate purpose. In so doing, she reveals to man the meaning.

The Church has contributed to promoting and continues to advocate for the defense of the dignity of the human person. She feels it is her duty to be the “sentinel” of man’s humanity, at a time in which the threats to humankind are not external but actually come from within man and are in his very heart. In spite of the difficulties and tensions existing in the Church’s relationship with the modern world, it must be recognized that the Church has always been an expert in humanity and has always been on man’s side. Never before has it appeared so clearly that the Church is on the side of man’s truth, and claims to be indispensable. Her essence is the proclamation of Christ, who is man’s truth and the meaning of history. It is for this reason that the Church strives to be a reliable companion for man, as she helps him to fulfill his intimate nature by combining nature and reason. And yet, modern culture tends to relegate her to the role of mere ethical and social agency. The Church today is aware that society needs her contribution. She also knows that she is best positioned to fulfill the specific task entrusted to her when she is not conceived as a minimal Church, providing a mere pastoral service, but when she is cognizant of her own identity, i.e. being the expression of charity and truth, so closely intertwined.

Unfortunately, not always has Christianity been presented or understood according to its genuine essence. Jesus Christ is not one God among many, but the only God who can respond to man’s most intimate need for salvation. His message is for the men of all time and all cultures—therefore and especially for the modern man, who believes that he can achieve salvation on his own but crumbles like sand when faced with illness, pain, or death.

If I look around me, I realize that the image of the Catholic Church is not always a clear reflection of Jesus’s gospel. This does not mean that this is not her true mission, and that this should be the commitment of each one of her members. Please allow me now to conclude with a significant reference by Gandhi to the mission of Christians. Gandhi is believed to have said, “I love and appreciate Jesus, although I am myself not a Christian. I would become one if only I saw a Christian behave like him.” And again, “Though I do not claim to be a Christian, the example of Jesus’s suffering is a factor in the composition of my undying faith in nonviolence, which rules all my actions, worldly and temporal. Jesus would have lived in vain and he would have died in vain if he did not teach us to regulate the whole of life by the eternal law of love.”