In this series of entries, Jacob Dreyer investigates the spatial forms of modernity in China, notably that of the Metropolis (e.g., Shanghai) and the Wasteland (e.g., Heilongjiang). In his last piece, he read the two regions through Schmitt’s dialectic of land and sea; here, he reads Shanghai through Dostoyevsky’s vision of the Crystal Palace; the next piece will subject the exterior, the “Great Northern Wasteland,” to a similar analysis.

If the goal of the project of modernity in China is ultimately the integration of the entire territory of PRC China into an urbanized “interior,” with no useless or wild zones, of universalizing the social practices of the metropolis, then an investigation into the unique spatial forms that did not emerge until modernity—and their shadow in consciousness, visible in the work of philosophers, writers, and architects—is necessary. As discussed in my previous post, Chinese literati have been exploring the territory since the beginning of civilization in Asia. In fact, it would not be inaccurate to say that the beginning of civilization is created by the initial architectural division between “inside” and “outside,”[1] created by architecture—physical edifices, no doubt, but also the structures of thought and language which tend to divide the world into two zones, interior and exterior. These two spaces, remarkably different in their effect on the psyche, are in dialectical relation, neither complete without the other. Ultimately, it is the dialectic between interior and exterior, between those voyagers who set out from the metropolis to the savage wilderness, on the one hand, and the strange bandits and marauders who rush through the forest into the streets of the city, on the other, that must be resolved in order to attain a utopian condition, e.g., the biopolitical task of housing over a billion individuals within a rationally articulated system.

If the goal of the project of modernity in China is ultimately the integration of the entire territory of PRC China into an urbanized “interior,” with no useless or wild zones, of universalizing the social practices of the metropolis, then an investigation into the unique spatial forms that did not emerge until modernity—and their shadow in consciousness, visible in the work of philosophers, writers, and architects—is necessary. As discussed in my previous post, Chinese literati have been exploring the territory since the beginning of civilization in Asia. In fact, it would not be inaccurate to say that the beginning of civilization is created by the initial architectural division between “inside” and “outside,”[1] created by architecture—physical edifices, no doubt, but also the structures of thought and language which tend to divide the world into two zones, interior and exterior. These two spaces, remarkably different in their effect on the psyche, are in dialectical relation, neither complete without the other. Ultimately, it is the dialectic between interior and exterior, between those voyagers who set out from the metropolis to the savage wilderness, on the one hand, and the strange bandits and marauders who rush through the forest into the streets of the city, on the other, that must be resolved in order to attain a utopian condition, e.g., the biopolitical task of housing over a billion individuals within a rationally articulated system.

What is an Interior?

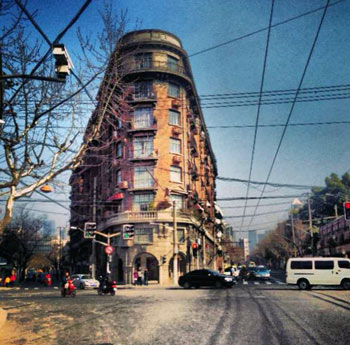

Shanghai, an endless set of cozy, small rooms and the habits and comforts, has for me assumed the contours of a grand interior: protective and soft, also a bit tedious, and the streets merely hallways within a home of sensations. The spatial interior of the city, certain inner city districts, typical boulevards and housing typologies, corresponds to a certain mentality, a convenient way of organizing one’s own thoughts. The 小市民 (petty urbanite) or 小资 (petty bourgeois) mentality characteristic of Shanghai could be described as “small minded”; indeed, the Chinese “小” means “little/small.” Above all a particle of the urban mass, the petty bourgeois is, well, petty: focused on economic gain, short-sighted, nostalgic. This attitude is created primarily by the myriad dividing borders that exist to regulate space in Shanghai, one of the most densely populated zones on the planet.[2] Privacy is nowhere to be found, and consequently one is always aware of the gaze of the others. This creates a social mechanism of self-regulation, with the constant goal of seeking to avoid unwanted attention from others. In space, these walls and barriers are the walls of buildings themselves; the thin walls of the old buildings, which mean that we always know what our neighbors are doing; the streets, channeling traffic in certain directions and along certain axes. In time, the compulsion to work constantly, which results in an awareness of the monetary value of any given hour of one’s time. In social life, networks of friends, one’s awareness of class, subdivision along the lines of native place or profession. In mental space, the pervasive influence of advertising. In Shanghai, we are never alone; there is always a light in the window just parallel to our own; and in the windows of office buildings, no matter how late at night. The consciousness of the bourgeois is thus, as Chinese usage correctly indicates, small, for the space within which one may move freely is small indeed. An awareness of one’s limitations defines the cautious, noncommittal attitude of the Shanghainese.

Of course, Shanghainese people do not use the word bourgeois as an insult. The dialect word (old color) is how we bourgeois call ourselves in the urban districts, Huangpu, Jing’an, Xuhui. The Shanghai Old Color, much like his European counterpart, is associated with certain styles, a preference for European style, drinking coffee rather than tea, wearing western suits, and dancing to the jazz music of the 30s. This character is succinctly defined in the writings of Shanghainese novelists such as Eileen Chang[3] and Wang Anyi,[4] or perhaps Sun Ganlu.[5] I myself, in an attempt to comprehend this attitude, took a job working at a marketing firm on Shanghai’s Bund, my days measured by the tolling of the bells in the Customs House,[6] to which I bicycled from my home in Jing’an Villa, bourgeois nest par excellence, full of the knowing cackles of Shanghai dialect and, on my return in the evening, the delicious smells of small fish simmering in sugar and oil.

A bourgeois, I watched my view of the world shrink, my hours defined as strictly as that of a prisoner in a golden cage, speaking to clients on the telephone and drinking endless coffees. This character, a modernist cliché come to life, has remained an archetype even as the city’s revolutionary forty years (1949–89) forced him in to hibernation, into pressing old and graying shirts, into secret underground dance clubs, into shining shoes with saliva, shoe polish being unavailable.

Although this figure may seem anachronistic, a holdover or refugee from another era, he really comes into definition only after the revolutionary period. When his identity was absolutely typical, there was nothing special or notable; it was not a choice that he wore a white shirt every day, but simply the required custom. It was only when nostalgia for a past time materialized itself as a luxury that this figure became clear. Defined entirely by the walls within which he operates, the limits that surround him like a cloak, only the interior of the city can give him comfort, the pleasure of an exquisite evening strolling down the boulevard. Although we may (and the Chinese revolutionaries did) see walls and confinements as intrinsically reactionary structures of capitalism and social division,[7] movement and flow requires infrastructure to flow through, aqueducts of experience, our great Shanghainese boulevards, Huaihai Road, Nanjing Road, Henan Road.

The “old color” looks with terror at the world outside of the city, the roiling interior of China, boiling with poverty and psychic wilderness, strange events and threatening people, and always the barely withheld threat of violence. Yes, our Shanghainese interior—a mental interior, as much as a spatial or even temporal one—is defined by the conditions of our confinement. But this gilded prison has been looked upon with nostalgia since the day that the cage was opened, with the paradoxical result not that the citizens left, but that peasants from the countryside swarmed in and camped out in the great houses, establishing primitive hutches for cooking in the hallways that capitalist slippers once trod, shirtlessly playing card games such as 斗地主[8] underneath chandeliers which no longer illuminate, but only gather dust. With Eileen Chang’s Shanghai (itself a memory transcribed from Hong Kong) nothing but a memory, the old color is fundamentally a pathetic figure, as in the writing of Wang Anyi. Shanghainese men are looked down on throughout China as being gutless. They and their way of life were overcome in the revolution, for Shanghai, the city of flow, stopped flowing for forty years, as the water of the Huangpu river became acrid with the soot of socialist factories. The lid firmly clamped on, the city could only ferment, stew in its own juices, decaying in memory both bitter and sweet. The mentality called Shanghainese, this interior was only firmly created when the door was closed and locked. Now the Shanghainese way of life is once more in danger of drifting away, or floating down the stream, which is, in a way, appropriate.

Leaving the Iron House

In the opening act of the Chinese modern, Lu Xun unforgettably evoked the perils of remaining in a sterile interior, the pre-modern Chinese mentality:

Imagine an iron house without windows, absolutely indestructible, with many people fast asleep inside who will soon die of suffocation. But you know since they will die in their sleep, they will not feel the pain of death.[9]

Our house is no prison. Rather than an iron house, the contemporary urban subject inhabits a structure similar to the Crystal Palace evoked by Dostoyevsky: a comfortable and amusing bubble. We never are quite sure what is on the outside. Distracted by certain reflections, sounds, and images, we see faintly filtering into our gilded cage, we yearn for the outside: the outside to the self, the outside to the city, the outside to work, the outside to the version of history that we inhabit. In China, as in the West, the idea of utopia has more often been a foil for critiques of the current order than a concrete set of proposals. The traditional Chinese idea of utopia, the peach blossom spring,[10] is unambiguously an idea of harmony with nature. However, the China that is forming today clearly displays a more complicated interplay between humans and their environment than these premodern myths. What remains unclear is exactly what does lie outside the house within which we slumber in afternoon languor, sunshine blunted by polluted clouds shining through the window.

Notes

1. For Hegel, “the earliest beginnings of architecture . . . are a hut as a human dwelling and a temple as an enclosure for the god and his community,” emphasis mine. In other words, the initial move of civilization is to create a wall between outside and inside, the origin of the dialectic in space. G. W. F. Hegel, Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art, trans. T.M. Knox, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), p. 76.

2. “The population density of Shanghai reached 3,030 people per square kilometer in 2009, up by 19.5 percent from 2000. This indicator rises to 16,000–44,000 people per square kilometer in central Shanghai, making the city one of the most crowded megacities in the world.” See Youde Gou, “Urbanisation and Disease Patterns in Shanghai,” LSE Cities website, November 2011.

3. The definitive novelist of bourgeois pre-revolutionary Shanghai, who left the city for Hong Kong following liberation. See the biographical entry “Eileen Chang” at the New York Review of Books website.

4. Wang Anyi, The Song of Everlasting Sorrow, trans. Michael Berry and Susan Chan Egan (New York: Columbia UP, 2010).

5. Sun is the hidden impressionist master of boulevard life in Shanghai. My idea of Shanghai as a city where life flows on endlessly is in large part derived from his writing. Sadly, he has not been translated as much as his work deserves. See the Sun Ganlu website (in Chinese).

6. Chinese art historian Wu Hung has claimed that this bell, erected over one hundred years ago, had a decisive influence on the understanding of the passage of time in Chinese modernity. See Wu Hung, “Monumentality of Time: Giant Clocks, the Drum Tower, the Clock Tower,” in Robert S. Nelson and Margaret Olin, eds., Monuments and Memory: Made and Unmade (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003,) pp. 107–32.

7. “After Dongming town in Shandong province was liberated, some 20,000 people organized themselves into shock brigades for the task of demolishing the wall surrounding the town, and they finished the job in just three days. ‘The jubilant masses kept shouting: we are no longer jailed!'” (“Dongming Town After Liberation,” People’s Daily, p. 2, June 15, 1946, cited in Wang Jun, Beijing Record: A Physical and Political History of the Planning of Modern Beijing [Beijing: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2010]).

8. “Fighting the landlord,” a game with roots in the cultural revolution. See the Wikipedia entry for Dou Dizhu for rules.

9. Lu Xun, “Preface to Call to Arms.”

10. Douwe Fokkema, Perfect Worlds: Utopian Fiction in China and the West (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2011).