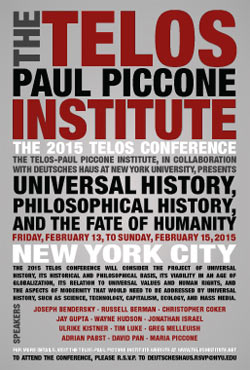

An earlier version of the following paper was presented at the 2015 Telos Conference. For additional details about upcoming Telos conferences and events, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

Luigi Sturzo (1871–1959) was an Italian priest, social reformer and the founder in 1919 of the Popular Party that later became the Christian Democratic Party, and social theorist who wrote extensively about history during the last century. Regarding history, Sturzo’s great contribution is his account of the formation and development of the “International Community” as one of the concrete forms of human society subject to its general laws. Sturzo locates the roots of this concept in the Christian revelation of human equality before God and the subsequent religious duty to love one’s neighbor in a manner that transcends the traditional boundaries of the ancient world. Thus the social values of the pre-Christian world are inverted, and human personality assumes the mantle previously held by the social and ethnic bonds of that era.

Luigi Sturzo (1871–1959) was an Italian priest, social reformer and the founder in 1919 of the Popular Party that later became the Christian Democratic Party, and social theorist who wrote extensively about history during the last century. Regarding history, Sturzo’s great contribution is his account of the formation and development of the “International Community” as one of the concrete forms of human society subject to its general laws. Sturzo locates the roots of this concept in the Christian revelation of human equality before God and the subsequent religious duty to love one’s neighbor in a manner that transcends the traditional boundaries of the ancient world. Thus the social values of the pre-Christian world are inverted, and human personality assumes the mantle previously held by the social and ethnic bonds of that era.

Admittedly, the notion of a Christian international society is at marked variance with the facts of history. As Sturzo reminds us, a fundamental dualism of political and religious powers was the novelty introduced with Christianity, and this diarchy—Sturzo’s term—has characterized every Christian civilization for two thousand years. Indeed, one could argue it was precisely this dualism that allowed political power to dissociate itself from religious authority over the course of the centuries and claim for itself not only autonomy, but also absolute autonomy over its subjects through the appropriation of its own personality. In any event, Sturzo concedes the modern State remained the central arbiter of power in the International Community up to his day.

But the State was not the only such power. In fact, the development of such bodies as the Permanent Arbitration Court, the Permanent Court of International Justice, the Pan-American Union, the British Commonwealth, and the League of Nations, reflected the evolution of a relatively new state of affairs that Sturzo describes as the interdependence of States. This development was premised for Sturzo on the fundamental law of Individuality-Sociality that underlies all human society: “The more individuals increase in conscious personality, the fuller the development of their associative qualities and forces; the fuller the development of such associative forces, the more the individuals develop and deepen the elements of their personality.”[1] Thus society crystallizes itself through a continuous process of action and reaction into a number of individual bodies, while at the same time the individual is socialized through the development of these same bodies. This variety leads Sturzo to claim it is simply not true that political power has to be concentrated in a single organism, or that such an organism has to be the State.

This vision does not mean that Sturzo thinks there should be no role afforded to States in the international realm. To the contrary, he claims that the State gains in stability to the extent that its power relies less on force than on law. Indeed, the achievement of “conscious personality” on the part of the various States is a key factor for Sturzo in the progress of the International Community towards its own organization and self-consciousness. But this very progress suggests that modern States are responding through the enactment of treaties and conventions to a reality beyond themselves. This reality, moreover, amounts to an “unwritten law,” or moral force that is oriented towards the protection of individual persons, and which becomes the objective rule of social life in the form of international law. The point here is that Sturzo discerns not only a tendency that underlies the development of the international community, but also a normative thread that runs throughout the heart of human history. In short, States are—and should be—deferring in a progressive manner to the basic datum of human personality, understood as both individual and social in light of its eternally evolving relations.

Near the end of Nationalism and Internationalism (1946), Sturzo writes: “We are going toward an international life in spite of our mistakes and failings.”[2] Thus, it appears, he envisages a natural progression of individuals toward an inevitably globalized single society. “This ‘multiple, simultaneous and continuative projection of individuals,’ which is society,” he writes at the beginning of Inner Laws of Society: A New Sociology (1944), “achieves itself in time, just as all individual activity is achieved through time. Human reality is process.”[3] But note here the reference not to “progress” but, instead, to “process.” “We say process, that is, succession, and not progress, nor evolution,” Sturzo writes, “because all human activity is individual, even if developing, as it does, collectively or by groups. Every individual activity is, above all, experience, experiment, the reduction of the experience of others into our own, really personal” (xvii–xviii). For Sturzo, then, “in associated life there are contemporaneously developments, arrest, renewals, involutions, all the stages that experience implies. Hence, there is not always progress, never a real regression, but in a relative sense both progress and regression, that is, experimentation and achievement” (xviii).

In Sturzo’s view, the ideas of progress and evolution presuppose a deterministic conception, which “denies the idea of individuality and of personal experience, and, hence, the idea of liberty, reducing the whole of human activity to a more or less unconscious necessity” (xix). Yet, he writes, “the concept of process as the succession of individual experiences, and also, through the individuals, of collective experiences, in no wise means that the individual is wholly free, without laws, and without limits. It means merely that within the laws and limits of his being and of the conditioning factors about him, he is not determined but self-determining, and by this very fact may be considered a creator of his own experience” (xix).

History, which Sturzo defines as the systematic and rational exposition of known events, is always incomplete: first, in his words, “because what we know of the past is never the whole past but a part, that which has been historicized, and this never accurately and never completely, so that critical revision is continuous and necessary” (xxvii); second, because the rational exposition through which known events are interpreted and systematized varies with different epochs, cultures and philosophical systems. “The historical datum, even if expressed by a single individual,” Sturzo maintains, “in order to be historical must find its repercussions in an ever-widening circle of individuals and assume a collective character” (xxvii). In other words: “The historical datum becomes a social element, inasmuch as either actually or as symbol or attribution it represents that human experience and activity which, once posited, continues to be experienced by a group in its further process” (xxvii).

In the concrete, then, we do not find society, but societies. “It is possible to conceive of an international society of all the peoples of the earth,” Sturzo writes, “but such a construction will not be a single society for all men, but a special society of States, or of peoples, on the specific plane of their political relationships, or else will lead to particular societies for determined purposes, cultural, economic, or otherwise” (19). For every social form tends to individuation and autonomy, the basis for which lies in the way groups distinguish themselves from other groups. As Sturzo puts it: “The element of distinction is a negative datum, which is rendered spiritual by the unitive principle, the social consciousness” (19).

The idea of mankind may arouse in us feelings of solidarity. But such feelings are not enough, in Sturzo’s view, to constitute a single society: “The differentiation would be lacking, which, as we have seen, is the negative moment necessary for a social unification” (21). The dynamism would be lacking, which can be found only in a properly individuated social form. “Yet,” he writes, “within the active totality of men we may conceive of a web of individuated societies, with ever widening relationships, so as to touch the idea of universality, without ever wholly achieving it” (21).

“For the same reason,” concludes Sturzo, “there is no true universal history, but only particular histories of different social groups” (21). What are called universal histories are no more than collections of particular histories, combined together from a particular angle, which can never unify them. In short: “Every history indicates the consciousness of a group in the concrete” (21).

Matthew Bagot is Associate Professor in the Department of Theology at Spring Hill College.

Notes

1. Luigi Sturzo, The International Community and the Right of War (New York: Howard Fertig, 1970), pp. 44–45.

2. Luigi Sturzo, Nationalism and Internationalism (New York: Roy Publishers, 1946), p. 271.

3. Luigi Sturzo, Inner Laws of Society: A New Sociology (New York: P.J. Kenedy & Sons, 1944), xvii. Subsequent page references will be cited parenthetically in the text.