By Jacob Dreyer · Monday, April 21, 2014 In this series of entries, Jacob Dreyer investigates the spatial forms of modernity in China, notably that of the Metropolis (e.g., Shanghai) and the Wasteland (e.g., Heilongjiang). In his last piece, he read the two regions through Schmitt’s dialectic of land and sea; here, he reads Shanghai through Dostoyevsky’s vision of the Crystal Palace; the next piece will subject the exterior, the “Great Northern Wasteland,” to a similar analysis.

If the goal of the project of modernity in China is ultimately the integration of the entire territory of PRC China into an urbanized “interior,” with no useless or wild zones, of universalizing the social practices of the metropolis, then an investigation into the unique spatial forms that did not emerge until modernity—and their shadow in consciousness, visible in the work of philosophers, writers, and architects—is necessary. As discussed in my previous post, Chinese literati have been exploring the territory since the beginning of civilization in Asia. In fact, it would not be inaccurate to say that the beginning of civilization is created by the initial architectural division between “inside” and “outside,”[1] created by architecture—physical edifices, no doubt, but also the structures of thought and language which tend to divide the world into two zones, interior and exterior. If the goal of the project of modernity in China is ultimately the integration of the entire territory of PRC China into an urbanized “interior,” with no useless or wild zones, of universalizing the social practices of the metropolis, then an investigation into the unique spatial forms that did not emerge until modernity—and their shadow in consciousness, visible in the work of philosophers, writers, and architects—is necessary. As discussed in my previous post, Chinese literati have been exploring the territory since the beginning of civilization in Asia. In fact, it would not be inaccurate to say that the beginning of civilization is created by the initial architectural division between “inside” and “outside,”[1] created by architecture—physical edifices, no doubt, but also the structures of thought and language which tend to divide the world into two zones, interior and exterior.

Continue reading →

By James King · Friday, April 18, 2014 The following paper was presented at the Eighth Annual Telos Conference, held on February 15–16, 2014, in New York City.

In the perspective of many, the prime criticism of liberal theories of democratic politics is that such theories proceed with a certain false and idealized individual in mind—these are great theories, elegant or hubristic, but at bottom, theories and not “real politics.” Political liberalism wrongly imagines the citizen to be a rational individual, sure of his will and life plans—or is this imagining wrong? The deeper critique holds that liberalism describes a peculiar individual, and that this individual really exists, but looks strangely like the liberal theorist and his class. Thus, for example, John Rawls’s theory of justice is suggested to fail women and the profoundly disabled. My critique today follows in this vein; I wish to add to this characterization of liberalism’s presumed political actor by showing him to be antiheroic. In the perspective of many, the prime criticism of liberal theories of democratic politics is that such theories proceed with a certain false and idealized individual in mind—these are great theories, elegant or hubristic, but at bottom, theories and not “real politics.” Political liberalism wrongly imagines the citizen to be a rational individual, sure of his will and life plans—or is this imagining wrong? The deeper critique holds that liberalism describes a peculiar individual, and that this individual really exists, but looks strangely like the liberal theorist and his class. Thus, for example, John Rawls’s theory of justice is suggested to fail women and the profoundly disabled. My critique today follows in this vein; I wish to add to this characterization of liberalism’s presumed political actor by showing him to be antiheroic.

Continue reading →

By Telos Press · Monday, April 14, 2014 The Telos-Paul Piccone Institute has several important events in the works for 2014, including conferences and symposia in Melbourne, Australia, Beijing, China, L’Aquila, Italy, and Irvine, California. At the recent Telos Conference in New York City, David Pan, Executive Director of the Institute, outlined the themes for this year’s conference.

Continue reading →

By Mark S. Weiner · Thursday, April 10, 2014 The following paper was presented at the Eighth Annual Telos Conference, held on February 15–16, 2014, in New York City.

As the final speaker after a fascinating day of talks, I’ll keep my comments brief. I’ll be addressing two questions about democracy raised by our conference description: first, “the reasons for its rarity and volatility”; and, second, “the factors that are essential for its stability.” For each question, I’ll try to provide a concise, mildly provocative answer from my perspective as a writer and scholar about constitutional law and comparative legal history. As the final speaker after a fascinating day of talks, I’ll keep my comments brief. I’ll be addressing two questions about democracy raised by our conference description: first, “the reasons for its rarity and volatility”; and, second, “the factors that are essential for its stability.” For each question, I’ll try to provide a concise, mildly provocative answer from my perspective as a writer and scholar about constitutional law and comparative legal history.

So why is democracy so rare and volatile? I think one answer we could give to this question is that democracy is volatile because the modern self is a legal achievement. There is nothing outside of law, including individual subjectivity. Instead, the modern self that lies at the center of liberal democratic practice developed only after a long historical process of dialectical negation and synthesis. In that process, a handful of societies, beginning in western Europe, transcended what in my most recent book I call the “rule of the clan.”

Continue reading →

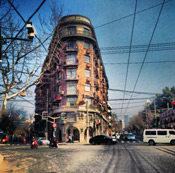

By Jacob Dreyer · Friday, April 4, 2014  The shadow of geography in modern Chinese thought is profound, for the understanding of a modern China above all relies on the interpretation of what China is. A population? A geography? A continental form of knowledge, modulated as cultural system? The interrogation of China’s two modern cities—Harbin and Shanghai[1]—reveals certain disparities in the approach toward geography and landscape, and the resultant subject position. Shanghai, whose name literally means “up against the sea,” and the soil of which is nearly entirely all the eroded dust from the banks of the Yangtze in the Chinese interior,[2] is the heir to the watery tradition of Jiangnan, the Yangtze region of water towns; Harbin, the frozen Siberian capital, was founded as an outpost in the middle of the “Great Northern Wasteland,” which has been tamed by the successive generations of labor fanning out from the transportation network of which Harbin is the center. Shanghai, then, has never been sufficiently solid or stable to be a capital; it errs on the avant-garde of flow, a slippery Atlantis. Harbin, with its gruff dialect, with its ripe and aged neighborhoods, with the earnest and clean faces glimpsed on the boulevards, is a city in which the earth has come to life. The shadow of geography in modern Chinese thought is profound, for the understanding of a modern China above all relies on the interpretation of what China is. A population? A geography? A continental form of knowledge, modulated as cultural system? The interrogation of China’s two modern cities—Harbin and Shanghai[1]—reveals certain disparities in the approach toward geography and landscape, and the resultant subject position. Shanghai, whose name literally means “up against the sea,” and the soil of which is nearly entirely all the eroded dust from the banks of the Yangtze in the Chinese interior,[2] is the heir to the watery tradition of Jiangnan, the Yangtze region of water towns; Harbin, the frozen Siberian capital, was founded as an outpost in the middle of the “Great Northern Wasteland,” which has been tamed by the successive generations of labor fanning out from the transportation network of which Harbin is the center. Shanghai, then, has never been sufficiently solid or stable to be a capital; it errs on the avant-garde of flow, a slippery Atlantis. Harbin, with its gruff dialect, with its ripe and aged neighborhoods, with the earnest and clean faces glimpsed on the boulevards, is a city in which the earth has come to life.

Continue reading →

By Telos Press · Wednesday, April 2, 2014 At this year’s Telos Conference in New York City, Telos Associate Editor Adrian Pabst outlined the theme of the upcoming Telos in Europe Conference, which will be held on September 5–8, in L’Aquila, Italy. This conference will focus on “The Idea of Europe,” and will offer speakers and attendees an opportunity to discuss Europe’s current crisis of identity. For complete details about the conference, as well as the full call for papers, please visit the conference page on the Telos Paul Piccone Institute website, located here.

Continue reading →

|

|

If the goal of the project of modernity in China is ultimately the integration of the entire territory of PRC China into an urbanized “interior,” with no useless or wild zones, of universalizing the social practices of the metropolis, then an investigation into the unique spatial forms that did not emerge until modernity—and their shadow in consciousness, visible in the work of philosophers, writers, and architects—is necessary. As discussed in my previous post, Chinese literati have been exploring the territory since the beginning of civilization in Asia. In fact, it would not be inaccurate to say that the beginning of civilization is created by the initial architectural division between “inside” and “outside,”[1] created by architecture—physical edifices, no doubt, but also the structures of thought and language which tend to divide the world into two zones, interior and exterior.

If the goal of the project of modernity in China is ultimately the integration of the entire territory of PRC China into an urbanized “interior,” with no useless or wild zones, of universalizing the social practices of the metropolis, then an investigation into the unique spatial forms that did not emerge until modernity—and their shadow in consciousness, visible in the work of philosophers, writers, and architects—is necessary. As discussed in my previous post, Chinese literati have been exploring the territory since the beginning of civilization in Asia. In fact, it would not be inaccurate to say that the beginning of civilization is created by the initial architectural division between “inside” and “outside,”[1] created by architecture—physical edifices, no doubt, but also the structures of thought and language which tend to divide the world into two zones, interior and exterior.  In the perspective of many, the prime criticism of liberal theories of democratic politics is that such theories proceed with a certain false and idealized individual in mind—these are great theories, elegant or hubristic, but at bottom, theories and not “real politics.” Political liberalism wrongly imagines the citizen to be a rational individual, sure of his will and life plans—or is this imagining wrong? The deeper critique holds that liberalism describes a peculiar individual, and that this individual really exists, but looks strangely like the liberal theorist and his class. Thus, for example, John Rawls’s theory of justice is suggested to fail women and the profoundly disabled. My critique today follows in this vein; I wish to add to this characterization of liberalism’s presumed political actor by showing him to be antiheroic.

In the perspective of many, the prime criticism of liberal theories of democratic politics is that such theories proceed with a certain false and idealized individual in mind—these are great theories, elegant or hubristic, but at bottom, theories and not “real politics.” Political liberalism wrongly imagines the citizen to be a rational individual, sure of his will and life plans—or is this imagining wrong? The deeper critique holds that liberalism describes a peculiar individual, and that this individual really exists, but looks strangely like the liberal theorist and his class. Thus, for example, John Rawls’s theory of justice is suggested to fail women and the profoundly disabled. My critique today follows in this vein; I wish to add to this characterization of liberalism’s presumed political actor by showing him to be antiheroic.  The shadow of geography in modern Chinese thought is profound, for the understanding of a modern China above all relies on the interpretation of what China is. A population? A geography? A continental form of knowledge, modulated as cultural system? The interrogation of China’s two modern cities—Harbin and Shanghai[1]—reveals certain disparities in the approach toward geography and landscape, and the resultant subject position. Shanghai, whose name literally means “up against the sea,” and the soil of which is nearly entirely all the eroded dust from the banks of the Yangtze in the Chinese interior,[2] is the heir to the watery tradition of Jiangnan, the Yangtze region of water towns; Harbin, the frozen Siberian capital, was founded as an outpost in the middle of the “Great Northern Wasteland,” which has been tamed by the successive generations of labor fanning out from the transportation network of which Harbin is the center. Shanghai, then, has never been sufficiently solid or stable to be a capital; it errs on the avant-garde of flow, a slippery Atlantis. Harbin, with its gruff dialect, with its ripe and aged neighborhoods, with the earnest and clean faces glimpsed on the boulevards, is a city in which the earth has come to life.

The shadow of geography in modern Chinese thought is profound, for the understanding of a modern China above all relies on the interpretation of what China is. A population? A geography? A continental form of knowledge, modulated as cultural system? The interrogation of China’s two modern cities—Harbin and Shanghai[1]—reveals certain disparities in the approach toward geography and landscape, and the resultant subject position. Shanghai, whose name literally means “up against the sea,” and the soil of which is nearly entirely all the eroded dust from the banks of the Yangtze in the Chinese interior,[2] is the heir to the watery tradition of Jiangnan, the Yangtze region of water towns; Harbin, the frozen Siberian capital, was founded as an outpost in the middle of the “Great Northern Wasteland,” which has been tamed by the successive generations of labor fanning out from the transportation network of which Harbin is the center. Shanghai, then, has never been sufficiently solid or stable to be a capital; it errs on the avant-garde of flow, a slippery Atlantis. Harbin, with its gruff dialect, with its ripe and aged neighborhoods, with the earnest and clean faces glimpsed on the boulevards, is a city in which the earth has come to life.