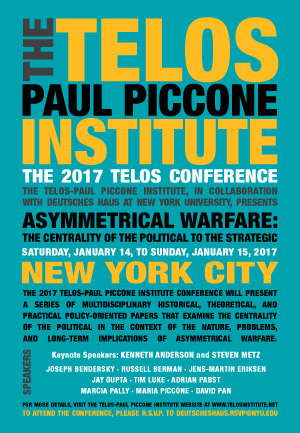

An earlier version of the following paper was presented at the 2017 Telos Conference, held on January 14–15, 2017, in New York City. For additional details about the conference as well as other upcoming events, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

Introduction: War and Politics

Introduction: War and Politics

The definition of asymmetry in asymmetrical warfare could, it seems, contribute to illuminating the link between war and politics, or war and peace. For Clausewitz, “War is a simple continuation of politics by other means.” Now, we could ask: what is the politics of asymmetrical warfare? Still following Clausewitz, war is “a wide-scale duel” and, as a duel or fight, war “takes two distinct forms: attack and defense.” Additionally, for Clausewitz, politics would be a form of “wide-scale commerce” between states. In his book Drone Theory, the French philosopher Grégoire Chamayou defines asymmetrical warfare as cynegetic (in other words, a form of hunt). He uses as an illustration the name of a recent model of unmanned vehicle: “the Predator,” le prédateur. But how can asymmetrical warfare be considered as war if the fight dynamic is absent? And if asymmetrical warfare is a manhunt, how could politics as commerce be possible?

What is Power? Between War and Politics

What do war and politics, or war and peace, have in common? What is the link that could explain the continuity or transition from one term to the other or the limitation of one term, war, by the other, politics? This common point would be a principle of power. Neither war, nor peace, nor politics would be possible without power. How can we define power? The French philosopher Raymond Aron gives, in his Peace and War between Nations, two definitions, one intentional and the other extensional, or in other words, a simple definition and a complex one where power is defined through its elements. Power would be seen not as a strength, but rather the influence that this strength can exert on other powers. Its elements would be: space (or territory); resources (human or material); and collective capability of action (or organization). Power could be defined by its material assets. A materialistic point of view could then be interesting to explain war, peace, politics, and asymmetrical warfare.

To join both definitions, we can say that the more a power has space, resources, or efficient organization, the more it has the capacity to influence. The double definition of power is interesting because, following Aron, it could serve to explain strength relationships from the tactical to the diplomatic level. A power in this case would be a singular weapon system, a squadron, an empire, a state, a city, or other entity. With this materialistic concept of power we could also speak of banditism or piracy and the links of these other “criminal practices” with guerrilla warfare and terrorism, like the drug trade conducted by the Columbian Revolutionary Armed Forces.

Power and thus war, peace, and asymmetrical warfare would, to follow Aron again, depend on its configuration of strength relationships, of which asymmetry would be one possible form. Symmetry, as a more equal relationship, seems to allow more possibility of dialogue, exchange, or commerce. Politics would thus be dependent on the type of configuration. However, we can also observe that war can never be entirely symmetrical or entirely asymmetrical. War as combat, or the dialectics between an attack and a defense, would be the confrontation of an offensive power with a defensive power. Attack and defense being different organizations of power, even warfare between two equivalent entities is therefore not entirely symmetrical.

However, the commerce between powers remains because before war there is peace, and war will eventually lead again to peace, a peace settled more or less to the advantage of one side. In war, mutual acknowledgment between powers, and therefore convention, is possible. Thus we have, in war, in this distinction of an offensive and a defensive power, an incomplete form of symmetry, a dissymmetry. This phenomenon of acknowledgment between powers could be illustrated by the concept and politics of the balance of powers. Even in war, the international order or system endures through this equilibrium. Without balance, a power such as the Roman Empire could finally implode, or push other powers to form a coalition against it, as in the Napoleonic wars.

Asymmetrical Warfare and Small War

Yet, acknowledgment, whether de facto or de jure, can exist only if an entity has enough power (in terms of space, resources, or organization) to be acknowledged. In this way, Aron explains in part the acknowledgment of the National Liberation Front of Algeria through its gain in power. And, as both Mao Zedong and Che Guevara observed, the aim of revolutionary forces is to take enough power to engage civil war. Asymmetrical warfare would be unconventional warfare because of its disequilibrium of forces and absence of acknowledgment. Asymmetrical warfare would thus be a form of warfare where the strength relationships would be particularly imbalanced, to such an extent that properly speaking there is no attack and no defense, but a manhunt dynamic instead.

Peace would therefore be made difficult by this absence of symmetry that makes commerce impossible. This is a situation we have seen in the nineteenth-century colonial wars. We can find a historical model for asymmetrical warfare (aside from obvious differences in techniques, communication, and weapon systems) in the Indian Mutiny. Therefore, this form of warfare could be defined, in bulk, as the opposition or, as says the French officer David Galula, the “Asymmetry between the Insurgent and the Counterinsurgent.” This insurgency against a domestic or foreign order could be also called an irregular war. Irregular war, like unconventional war, appears to be caused by an imbalance of powers.

To be fair, we could also say that an action or war could be unconventional without necessarily being asymmetrical, or vice versa. For example, a war crime or other action contrary to “rules of engagement” is unconventional but does not change the fundamental equivalence of the opponents. The example imagined by Mao Zedong, of rebel or guerrilla forces respecting conventions concerning the treatment of prisoners, is also perfectly conceivable. However, guerrilla and terrorist tactics show that it is not always favorable to a weaker power to respect rules or laws that are established or enforced to the advantage of a stronger power. Tactically speaking, an asymmetrical approach would thus consist of using light forces against a stronger adversary’s back lines, avoiding fighting if possible, and striking where the adversary is most vulnerable, such as its logistical structures and civilian population.

In fifteenth-century Hungary or Valchia (near Transylvania), these tactics were seen as totally conventional or regular when used against the Ottoman forces by the famous Vlad Tepes (a.k.a. Dracula). These tactics, conceptualized after the 30 Years War in the seventeenth century, were called “small war,” before becoming known in the nineteenth century against Napoleon in Spain as guerrilla. The case of Eastern Europe is interesting in the sense of these methods being put into general use by a larger power. Though considered shameful in another context or period, these tactics seemed conventional and regular in another time.

If the history of small war can show us one thing, it is that the most effective way to combat light, mobile forces is with other light, mobile forces—to protect and secure logistics, the civilian population and therefore political commerce, and peace as political order. Counter-insurgency would thus be a form of pacification. Also, the aim of counter-insurgency is less to react against insurgency than to protect peace or political order. In this way, asymmetry is at the structure of symmetry and politics and peace. As says Machiavelli: “there cannot be good laws where there are not good arms.”

Conclusion: Resettling a Balance of Power

Peace and war thus occupy a continuum of relationships going from an asymmetry to a symmetry of powers. Peace can be imposed, but this peace would not be possible without acknowledgment and commerce between powers and thus the resettlement of the balance of powers. If it is necessary to use light forces, such as present-day special forces, it is also necessary to form alliances with local populations and settle a political order, even if this order gives an advantage to one side. This is the way of colonization: divide et impera, divide and conquer, diviser pour mieux régner.

However, if pacification calls for the use of small-war methods, we should be aware of their potential dangers. These tactics, as says Basil Liddel Hart, undermine peace and order, and they are therefore appropriate to insurgency and thus asymmetrical warfare. This leads to the question of whom to choose as an ally. If international politics is a politics of powers, arming today’s allies could be arming tomorrow’s enemies. But the point of view is here strictly conceptual. It may be preferable now to leave practice to the practitioners.