By Alain de Benoist · Friday, April 10, 2020 The following essay originally appeared in Valeurs actuelles on April 2, 2020, and is published here in English translation by permission of the author. Translated by Russell A. Berman.

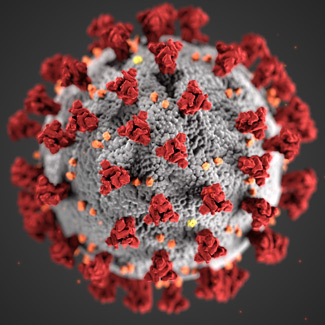

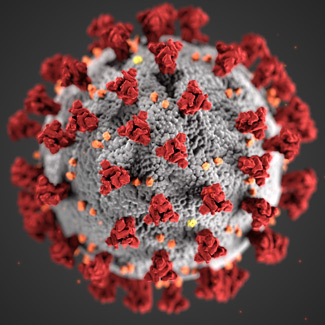

History is always open, as everyone knows, and this makes it unpredictable. Yet in certain circumstances, it is easier to see the middle and long term than the near term, as the coronavirus pandemic shows well. For the short term, one surely imagines the worst: saturated health systems, hundreds of thousands, even millions of dead, ruptures of supply chains, riots, chaos, and all that might follow. In reality, we are being carried by a wave and no one knows where it will lead or when it will end. But if one looks further, certain matters become evident. History is always open, as everyone knows, and this makes it unpredictable. Yet in certain circumstances, it is easier to see the middle and long term than the near term, as the coronavirus pandemic shows well. For the short term, one surely imagines the worst: saturated health systems, hundreds of thousands, even millions of dead, ruptures of supply chains, riots, chaos, and all that might follow. In reality, we are being carried by a wave and no one knows where it will lead or when it will end. But if one looks further, certain matters become evident.

It has already been said but it is worth repeating: the health crisis is ringing (provisionally?) the death knell of globalization and the hegemonic ideology of progress. To be sure, the major epidemics of antiquity and the Middle Ages did not need globalization in order to produce tens of millions of dead, but it is clear that the generalization of transportation, exchanges, and communications in the contemporary world could only aggravate matters. In the “open society,” the virus is very conformist: it acts like everyone else, it circulates—and now we are no longer circulating. In other words, we are breaking with the principle of the free movement of people, goods, and capital that was summed up in the slogan “laissez faire,” i.e., let it go, let it pass. This is not the end of the world, but it is the end of a world.

Continue reading →

By Russell A. Berman · Thursday, April 9, 2020  Once upon a time, there was an illusion that the state would disappear. It was the fiction Marxists told each other at bedtime, and it was the lie of the Communists, once they had seized state power. For even as they built up their police apparatus and their archipelago of gulags, they kept promising that one day the state would eventually disappear. Once upon a time, there was an illusion that the state would disappear. It was the fiction Marxists told each other at bedtime, and it was the lie of the Communists, once they had seized state power. For even as they built up their police apparatus and their archipelago of gulags, they kept promising that one day the state would eventually disappear.

Of course, in a sense, they were right because Communism ended and so did the Communist states in Russia and Eastern Europe. Yet the death of those regimes is in no way an argument for the death of statehood itself.

The state is the expression of sovereignty, and sovereignty is the ability of national communities to decide their own fates. Such independence is far from obsolete, and certainly not for the countries on the eastern flank of the European Union. After years of Russian occupation, they have regained their state sovereignty. They will continue to insist on it, and rightly so.

Continue reading →

By Saladdin Ahmed · Wednesday, March 18, 2020  There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe. There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe.

Perhaps it is inappropriate to joke about COVID-19. However, the pandemic’s increasing traumatic effects across the world are precisely the reason we should also joke about it. Those of us who have lived through calamities realize that sarcasm, far from being disrespectful to human suffering and loss, can be nobler than any serious expression that will inevitably undermine the actual experience. Those of us who have lived through something along the lines of the following examples know the indispensability of sarcasm: living defiantly in the face of the terror devised by a totalitarian regime; being a political prisoner under a fascist regime; taking the first physical steps to leave every place and everyone one has ever known; or, crossing bloody borders in a mythic-like quest in search of a place where one can continue to exist, even if merely as an ontological mistake. Humor is almost a natural coping mechanism when everydayness becomes a struggle for survival. One can easily observe that despite the apparent contradiction, there is more laughter among political prisoners who are facing death than among the affluent in luxurious social settings that are prepared specially to prevent boredom and dread.

Continue reading →

By Telos Press · Thursday, October 20, 2016 “Fraternity means that the father no longer sacrifices the sons; instead the brothers kill one another. Wars between nations have been replaced by civil war. The great settling of accounts, first under national ‘pretexts,’ led to a rapidly escalating world civil war.”

—Ernst Jünger, Eumeswil

Continue reading →

By David Pan · Sunday, June 26, 2016 Walk around Berlin these days and you will find that you will hear almost as much English being spoken on the streets as German. While some describe this situation as a sign that Berlin has now become a cosmopolitan city, this very interpretation reveals precisely the attitude that has led to the rise of English in Germany. To speak English is to be cosmopolitan, and to speak German is to be provincial, and so it becomes a mark of pride to converse in English rather than one’s native German, at least for a certain segment of the population. And therein lies the problem. For it is precisely that segment of global business people, academics, and bureaucrats against whom nationalist sentiment has been rising all over Europe amongst the monolinguals who see themselves as excluded from the European project.

Continue reading →

By Andrew M. Wender · Friday, April 3, 2015  The emerging exhaustion of the Westphalian paradigm of state sovereignty intimates the profoundly contestable and contingent character of modern, Western claims for a universal model of history. Over several centuries, the state has embodied and enforced foundational postulates, such as the pre-eminence of the individual knowing subject, and the imagined divide between religious and secular realms of existence and authority (with the latter sphere effectively internalizing the sacred import of the former). At present, though, the state’s tenuousness, and yet in key instances fierce tenacity, amidst a world of potent transnational forces, portends the urgency for alternative conceptions of the meaning and arrangement of human life. Contemporary Middle Eastern quandaries are especially illustrative of this predicament: for example, the disintegration (as in Iraq, Syria, Libya) or, then again, coercive retrenchment (viz., Egypt) of state formations and nationalist identities; or, to take another sort of instance, the chimerical prospects for coexistence, or even bare existence, among conflicting national communities, as in Israel/Palestine. Are there political paradigms beyond the Westphalian state that could help to integrate plural traditions in pursuit of less exclusionary, and more just, historical possibilities? The emerging exhaustion of the Westphalian paradigm of state sovereignty intimates the profoundly contestable and contingent character of modern, Western claims for a universal model of history. Over several centuries, the state has embodied and enforced foundational postulates, such as the pre-eminence of the individual knowing subject, and the imagined divide between religious and secular realms of existence and authority (with the latter sphere effectively internalizing the sacred import of the former). At present, though, the state’s tenuousness, and yet in key instances fierce tenacity, amidst a world of potent transnational forces, portends the urgency for alternative conceptions of the meaning and arrangement of human life. Contemporary Middle Eastern quandaries are especially illustrative of this predicament: for example, the disintegration (as in Iraq, Syria, Libya) or, then again, coercive retrenchment (viz., Egypt) of state formations and nationalist identities; or, to take another sort of instance, the chimerical prospects for coexistence, or even bare existence, among conflicting national communities, as in Israel/Palestine. Are there political paradigms beyond the Westphalian state that could help to integrate plural traditions in pursuit of less exclusionary, and more just, historical possibilities?

Continue reading →

|

|

History is always open, as everyone knows, and this makes it unpredictable. Yet in certain circumstances, it is easier to see the middle and long term than the near term, as the coronavirus pandemic shows well. For the short term, one surely imagines the worst: saturated health systems, hundreds of thousands, even millions of dead, ruptures of supply chains, riots, chaos, and all that might follow. In reality, we are being carried by a wave and no one knows where it will lead or when it will end. But if one looks further, certain matters become evident.

History is always open, as everyone knows, and this makes it unpredictable. Yet in certain circumstances, it is easier to see the middle and long term than the near term, as the coronavirus pandemic shows well. For the short term, one surely imagines the worst: saturated health systems, hundreds of thousands, even millions of dead, ruptures of supply chains, riots, chaos, and all that might follow. In reality, we are being carried by a wave and no one knows where it will lead or when it will end. But if one looks further, certain matters become evident.  There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe.

There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe.  The emerging exhaustion of the Westphalian paradigm of state sovereignty intimates the profoundly contestable and contingent character of modern, Western claims for a universal model of history. Over several centuries, the state has embodied and enforced foundational postulates, such as the pre-eminence of the individual knowing subject, and the imagined divide between religious and secular realms of existence and authority (with the latter sphere effectively internalizing the sacred import of the former). At present, though, the state’s tenuousness, and yet in key instances fierce tenacity, amidst a world of potent transnational forces, portends the urgency for alternative conceptions of the meaning and arrangement of human life. Contemporary Middle Eastern quandaries are especially illustrative of this predicament: for example, the disintegration (as in Iraq, Syria, Libya) or, then again, coercive retrenchment (viz., Egypt) of state formations and nationalist identities; or, to take another sort of instance, the chimerical prospects for coexistence, or even bare existence, among conflicting national communities, as in Israel/Palestine. Are there political paradigms beyond the Westphalian state that could help to integrate plural traditions in pursuit of less exclusionary, and more just, historical possibilities?

The emerging exhaustion of the Westphalian paradigm of state sovereignty intimates the profoundly contestable and contingent character of modern, Western claims for a universal model of history. Over several centuries, the state has embodied and enforced foundational postulates, such as the pre-eminence of the individual knowing subject, and the imagined divide between religious and secular realms of existence and authority (with the latter sphere effectively internalizing the sacred import of the former). At present, though, the state’s tenuousness, and yet in key instances fierce tenacity, amidst a world of potent transnational forces, portends the urgency for alternative conceptions of the meaning and arrangement of human life. Contemporary Middle Eastern quandaries are especially illustrative of this predicament: for example, the disintegration (as in Iraq, Syria, Libya) or, then again, coercive retrenchment (viz., Egypt) of state formations and nationalist identities; or, to take another sort of instance, the chimerical prospects for coexistence, or even bare existence, among conflicting national communities, as in Israel/Palestine. Are there political paradigms beyond the Westphalian state that could help to integrate plural traditions in pursuit of less exclusionary, and more just, historical possibilities?