This is the fourth in a series of posts that introduce the thought of historian Martin J. Sklar, as a prelude to a print symposium on his life and work in a future issue of Telos. Earlier excerpts of Sklar’s writing appear in the first, second, and third posts. For a fuller introduction, refer to the head note to the first TELOSscope post. As a researcher, Sklar was a historian of the United States, including its role in the world, particularly (from the late nineteenth century) as a promoter and guarantor (on balance) of a global system of expanding economic and political freedom. As a reader and informed commentator on international affairs, he was also deeply interested in broader issues in world history, particularly insofar as they shaped contemporary global conflicts. (Among the several dozen of Sklar’s books that I inherited are heavily marked and annotated copies of the following: John Yoo, War by Other Means: An Insider’s Account of the War on Terror; Philip Bobbitt, Terror and Consent; Bernard Lewis, The Middle East: A Brief History of 2,000 Years; and Niall Ferguson, Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire.) The following excerpts from a letter to John Yoo reflect Sklar’s evolving understanding of what he understood as an ongoing U.S. (and Western) war against Islamic imperialism. Of particular interest is his conceptualization of various sectarian, and even nominally secular, movements as sometimes-competing branches of an expansive, totalitarian movement.

|

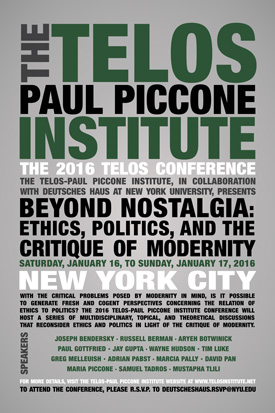

Traveling in Paris, Judith Butler published a “letter” dated November 14, in English on the Verso blog and in French in Libération, the day after the ISIS attacks, entitled “Mourning becomes the Law.” The short text treats two phenomena and argues for a connection between them: the process of mourning the victims of the attacks and the expansion of counter-terrorist practices by the state. Butler’s thesis is that the shared grieving of the dead served exclusively as a vehicle to justify amplified police powers: in this sense, mourning becomes the law, or at least law enforcement. A close look at her claims, however, shows significant deficiencies in the account of mourning and an important misreading of the Parisian response. In his essay “Carl Schmitt on Friends, Enemies and the Political,” Andrew Norris inquires into the question that I have been interested in for quite some time: political friendship in Carl Schmitt’s political philosophy. Schmitt’s interpreters usually focus on the issue of enmity in his concept of the political, not least because Schmitt himself elaborates on the existential significance of political enmity much more extensively. From a conceptual point of view, however, political friendship should be viewed as at least equally relevant a part of Schmitt’s account of the political. The specific criterion of the political is famously the distinction “between friend and enemy,” not simply an indefatigable presence of political enmity. Norris should be lauded for his attempt to foreground a crucial, though still insufficiently explored, notion of a political (public) friend in Schmitt’s Concept of the Political. The following paper was presented at the 2016 Telos Conference, held on January 16–17, 2016, in New York City. For additional details about upcoming conferences and events, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

Moral relativists can assume a subjective or a contextual point of view. If they assume a subjective point of view, one might describe their theories or hypotheses as nihilistic. Nihilists recognize no transcendent moral values and no moral facts. According to them, predicates, such as right or wrong, or good or bad, have no independent reference. So nihilists recognize no significant moral difference between, for example, the deliberate killing of the objectively innocent, which is considered murder by most civilized people, and killing in self-defense. For them, even the principle of the presumption of innocence would be vacuous.

Michel Houellebecq’s novel Submission raises important questions about the cultural crises of modernity. It reflects on the dialectics of post-secularism and post-democracy in ways that have become particularly salient in light of the terror attacks in Paris and San Bernadino. Beginning with Vincent Lloyd’s post today, TELOSscope presents a series of discussions of the novel that will appear over the next several days. The violence of November 13, 2015, in Paris was met with an avalanche of grief and sympathy from around the world. Similar feelings followed the attack on Charlie Hebdo several months earlier. Paris is an iconic and beloved city; to see blood and bullet holes on the streets of Paris caused pain. Or rather, it causes professions of emotion. In an age of personal mediation, when we are expected to advertise our feelings about world events nearly in real time through tweets and Facebook posts, it is an open question how much feelings are felt—though they are most certainly performed. Affect circulates with ever increasing velocity, but such affect is increasingly shallow, more like a shared way of talking than anything having to do with inwardness. This does not mean mediated emotions are insignificant. As leftist critics of such public mourning charge, shared ways of talking about the world lead to shared ways of seeing the world and can ultimately legitimate violent ways of acting in the world. |

||||

|

Telos Press Publishing · PO Box 811 · Candor, NY 13743 · Phone: 212-228-6479 Privacy Policy · Data Protection Copyright © 2024 Telos Press Publishing · All Rights Reserved |

||||

While the expression “moral relativism” means different things to different people, I offer the following characterization of it. By “moral relativism,” I understand a normative view that explains people’s incommensurable moral judgments based on their subjective preferences or on different action-guiding contexts. Moral relativists deny that value judgments can be universally justified. Therefore, for them, value judgments have neither objective universal truth-value nor universal moral import. That is, these judgments are neither true nor false, nor right or wrong for everyone. For some moral relativists even to raise the possibility of moral disagreement across different cultures or communities would be simply moot.

While the expression “moral relativism” means different things to different people, I offer the following characterization of it. By “moral relativism,” I understand a normative view that explains people’s incommensurable moral judgments based on their subjective preferences or on different action-guiding contexts. Moral relativists deny that value judgments can be universally justified. Therefore, for them, value judgments have neither objective universal truth-value nor universal moral import. That is, these judgments are neither true nor false, nor right or wrong for everyone. For some moral relativists even to raise the possibility of moral disagreement across different cultures or communities would be simply moot.  Today’s world is witnessing a noticeable intensification of hostilities and confrontations on many fronts of international relations. A revisionist and neo-imperialist Russia, annexing Crimea and staging a cynical proxy war in Eastern Ukraine in 2014, is challenging the very foundations of the post–Cold War international order. The Syrian “quagmire,” which began in 2011, created a space for the emergence and gradual establishment of the so-called Islamic State (ISIS), now widely recognized as the paramount terrorist organization threatening the security architecture in the Middle East as well as Europe. Terrorist attacks in France, Egypt, Mali, Tunisia, Lebanon, and other countries have been widely and justifiably interpreted as warnings signaling that Europe (or the West in general) is unable to cope with its new enemies. The chaos and uncertainty that ensued after the flood of refugees and migrants into Europe only exacerbated the perception of weakness and unwillingness on the part of the Western leaders to tackle these challenges seriously. In this alarming context, political philosophy once again gains significance as an existential occupation. This is the reason why a re-evaluation of the controversial oeuvre of Carl Schmitt, the thinker who articulated some of the most acute criticisms of modern liberalism, is so timely.

Today’s world is witnessing a noticeable intensification of hostilities and confrontations on many fronts of international relations. A revisionist and neo-imperialist Russia, annexing Crimea and staging a cynical proxy war in Eastern Ukraine in 2014, is challenging the very foundations of the post–Cold War international order. The Syrian “quagmire,” which began in 2011, created a space for the emergence and gradual establishment of the so-called Islamic State (ISIS), now widely recognized as the paramount terrorist organization threatening the security architecture in the Middle East as well as Europe. Terrorist attacks in France, Egypt, Mali, Tunisia, Lebanon, and other countries have been widely and justifiably interpreted as warnings signaling that Europe (or the West in general) is unable to cope with its new enemies. The chaos and uncertainty that ensued after the flood of refugees and migrants into Europe only exacerbated the perception of weakness and unwillingness on the part of the Western leaders to tackle these challenges seriously. In this alarming context, political philosophy once again gains significance as an existential occupation. This is the reason why a re-evaluation of the controversial oeuvre of Carl Schmitt, the thinker who articulated some of the most acute criticisms of modern liberalism, is so timely.