By Russell A. Berman · Monday, August 8, 2022 The following comments refer to Mathieu Slama’s “How Brilliant Scientists Damage Democracy,” which appears here.

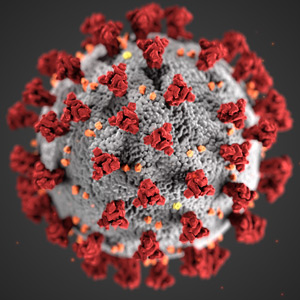

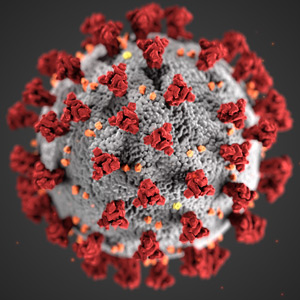

Among the many features of the COVID crisis, one stands out as particularly consequential: the attribution of ultimate and exclusive authority to science. Public statements abounded urging that we “follow the science,” and signs popped up on front lawns across the country advertising that the residents “believe in science”—as if science were a matter of belief rather than skepticism, observation, and experimentation. There was of course little attention to alternative scientific claims or debates within science. Instead of a scientific event, we witnessed the assertion of authority by way of the invocation of science or of what came to pass as “science.” The mandate to “follow the science” blindly has come to mean “follow the leader,” with no questions asked.

For large swaths of the public, the scientific label carries with it the implication of veracity: science, as opposed to religion (which is otherwise the proper subject matter of belief), is truth. Indeed the equation is a formula for modernity, which is why bizarre variants of modernization repeatedly cast themselves in the role of science: for Communism, the “science of Marxism-Leninism,” and for Nazis, “race science.” Nor do we have to look that far afield to those extreme cases in order to find reason to question the absolute truth claim of science. One can point to scandals like the Tuskegee experiment and to the regular reports of fraud and retractions, even in the most prestigious scientific journals. Just recently one reads that research reported in the journal Nature concerning Alzheimer’s may have been fraudulent. Following that science probably wasted millions of research dollars.

Continue reading →

By David Pan · Monday, August 1, 2022  Concerns about inflation can lead us to exaggerate the role of money in the economy. In his essay on “Three Rival Versions of Monetary Enquiry,” in Telos 194, Edward Hadas argues that money is not at the center of economics. Instead, economics is fundamentally about what he calls the “Great Exchange,” in which people offer labor that changes the world and the world in return provides gifts to people in the form of goods and services. At its basis, this exchange involves the relationship between humans and nature, as well as the ways in which humans decide to manage this relationship. Though it can go on with or without money, money is very useful for managing the individual elements of the Great Exchange. As the mediator of the details of the Great Exchange, money is in fact neutral, neither a nefarious underminer of human relations nor a key to prosperity. Concerns about inflation can lead us to exaggerate the role of money in the economy. In his essay on “Three Rival Versions of Monetary Enquiry,” in Telos 194, Edward Hadas argues that money is not at the center of economics. Instead, economics is fundamentally about what he calls the “Great Exchange,” in which people offer labor that changes the world and the world in return provides gifts to people in the form of goods and services. At its basis, this exchange involves the relationship between humans and nature, as well as the ways in which humans decide to manage this relationship. Though it can go on with or without money, money is very useful for managing the individual elements of the Great Exchange. As the mediator of the details of the Great Exchange, money is in fact neutral, neither a nefarious underminer of human relations nor a key to prosperity.

Continue reading →

By Telos Press · Monday, March 22, 2021 To read more in depth from Telos, subscribe to the journal here.

On The Agenda with Steve Paikin, the discussion about governmental responses to the COVID-19 pandemic turned to Thomas Brussig’s recent editorial “Risk More Dictatorship,” originally published in the Süddeutsche Zeitung and translated into English in TelosScope. Listen to the discussion here, and read Brussig’s full essay here, along with Russell Berman’s commentary on it here.

Continue reading →

By Russell A. Berman · Monday, March 8, 2021 To read more in depth from Telos, subscribe to the journal here.

A distinctive feature of public debate in Germany involves prominent literary authors, especially novelists, expounding on current political matters in major newspapers. Thomas Brussig’s essay “Risk More Dictatorship,” translated here, belongs to this genre. Known especially for his satire of East Germany, Heroes Like Us, Brussig chose a provocative title that seems to echo and respond to Chancellor Willy Brandt’s appeal more than fifty years ago to “risk more democracy.” Brandt was speaking in 1969 at a pivotal moment in the history of West Germany, indeed of the whole world, in the face of the protests during the previous year; Brussig in contrast appeals for “more dictatorship” in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, which he depicts as a potentially similar turning moment, with an accelerated “learning process,” that calls old certainties into question. These include the “end of history” claim that liberal democracy is inevitable; Brussig suggests that the “impotence” of democracies in the face of the pandemic raises the question as to whether other forms of government might be superior. The Chinese model of dictatorship casts a shadow across the essay. A distinctive feature of public debate in Germany involves prominent literary authors, especially novelists, expounding on current political matters in major newspapers. Thomas Brussig’s essay “Risk More Dictatorship,” translated here, belongs to this genre. Known especially for his satire of East Germany, Heroes Like Us, Brussig chose a provocative title that seems to echo and respond to Chancellor Willy Brandt’s appeal more than fifty years ago to “risk more democracy.” Brandt was speaking in 1969 at a pivotal moment in the history of West Germany, indeed of the whole world, in the face of the protests during the previous year; Brussig in contrast appeals for “more dictatorship” in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, which he depicts as a potentially similar turning moment, with an accelerated “learning process,” that calls old certainties into question. These include the “end of history” claim that liberal democracy is inevitable; Brussig suggests that the “impotence” of democracies in the face of the pandemic raises the question as to whether other forms of government might be superior. The Chinese model of dictatorship casts a shadow across the essay.

Continue reading →

By Bruno Retailleau · Tuesday, January 26, 2021 These remarks were published in Le Figaro on January 8, 2021, and appear here with permission of the author. Translated by Russell A. Berman. Footnotes have been added for clarification by the translator, whose introductory comments are here.

In a democracy, liberty always goes hand in hand with responsibility. Donald Trump’s responsibility for the outbreak of violence on Capitol Hill is clear. Minimizing that responsibility, as Marine Le Pen did by asserting that the American president did not “gauge the impact of his words” is the false politics: Because it ignores that in our agitated democracies, facing an exhausted people, moderating one’s words constitutes the premier obligation of responsible politicians. It is more than a matter of civility; it is an urgent civic necessity, if we do not want to see the battle of tweets degenerate into a war of all against all.

Yet indignation is not enough. We also have to understand. What do we see on the other side of the Atlantic? An ailing democracy, to be sure. Ailing from an epidemic of anger, of which the violence at the Capitol was by no means the first wave, nor is America the only “cluster” of this epidemic, since it has already spread across the rest of the Western world.

Continue reading →

By Norbert Bolz · Wednesday, October 14, 2020 Are we living once more in a Weimar Republic that no longer knows a center? The toxic climate of public opinion suggests just that. The language of irreconcilability allows some to speak of “covid idiots,” while others see our politics as heading toward dictatorship. And even government pronouncements are sounding more authoritarian, as with the call for a “tightening of the reins” that Bavarian Prime Minister Söder repeated after the chancellor.

Panic and hysteria are the reliable companions to nearly every major political theme today. But of course, corona is central. The most important political effect of the pandemic could well be the growing readiness to endure whatever may come. By contrast, the “corona rebels” wanted to set an example over the weekend. Their protest drew motivation from the impression that with the slogan “because of corona,” one can at any time call a state of emergency, in which freedom and democracy then no longer play a role.

Continue reading →

|

|

A distinctive feature of public debate in Germany involves prominent literary authors, especially novelists, expounding on current political matters in major newspapers. Thomas Brussig’s essay “Risk More Dictatorship,”

A distinctive feature of public debate in Germany involves prominent literary authors, especially novelists, expounding on current political matters in major newspapers. Thomas Brussig’s essay “Risk More Dictatorship,”